- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Mokopirirakau Kahutarae

Mokopirirakau kahutarae

Black-eyed gecko

Mokopirirakau kahutarae

(Whitaker, 1985)

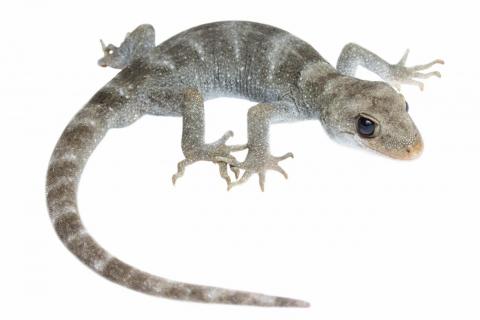

Length: SVL up to 96mm, with the tail being equal to the body length

Weight: up to 15 grams

Description

A large, and striking gecko with distinctive jet-black eyes, hailing from the high-montane country of the northern South Island. This species along with several other Mokopirirakau truly push the limit of gecko physiology living high up in the snow-covered peaks of the alpine zone (~2,000m asl).

These geckos are characterised by their grey or olive-grey dorsal surfaces, which often exhibit pale blotches, chevrons, or transverse bands, which run down the back and tail. These can be distinct or indistinct and are sometimes edged with black. Pale or dark speckles are sometimes present, but are typically not as distinct as those seen in the hura te ao gecko (Mokopirirakau galaxias). Lateral surfaces are typically olive-grey, transitioning to a pale grey toward the mid or lower portion of the lateral surfaces. The lateral surfaces are also sometimes speckled. The ventral surface is pale grey-white and mostly uniform, sometimes with speckles. As the name implies, the eyes of black-eyed geckos are vivid black, whereas the recently-discovered hura te ao gecko (Mokopirirakau galaxias) possesses dark brown eyes. Additionally, the black-eyed gecko has more prominent brillar folds (eye hood) and supraciliaries (scales located above the eyes)(Knox et al. 2021). Mouth interior pale red or pink, with a pale pink, red, or orange tongue (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

Can be differentiated from co-occurring gecko species by their dark eyes, a feature that is only shared by the closely-related hura te ao gecko (Mokopirirakau galaxias).

Life expectancy

Largely unknown, however, captive Mokopirirakau have frequently been known to live for upwards of 25 years, with some individuals topping the records at 40+ (D. Keal pers. comm 2016). The maximum age for wild animals is not known, however, it is likely that they can live at least as long as captive animals, if not longer.

It is theorised that alpine populations of Mokopirirakau may have longer lifespans than their lowland cousins due to the reduced metabolic activity of these species over extended periods of time. If this is the case it wouldn't be unfair to assume that these species could live well into their 80s, or even reach ages in excess of 100 years.

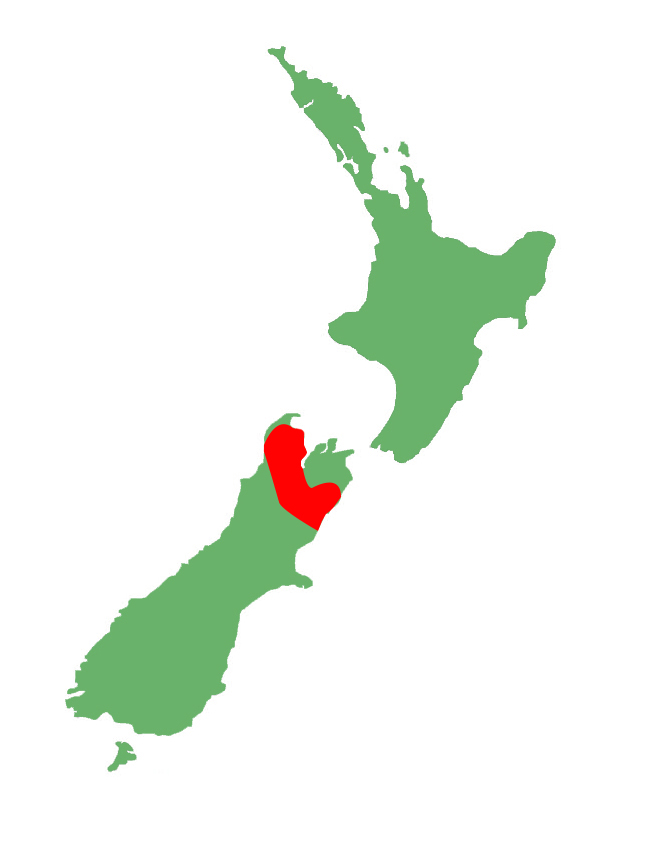

Distribution

Nelson-Marlborough and western Kaikoura. Known from both the Seaward Kaikōura Range and Inland Kaikōura Range, Nelson Lakes National Park, Mt Arthur, Matiri Range and, Lockett Range. It is probable that this species occurs elsewhere, such as North Canterbury, but is yet to be found (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

Ecology and habitat

Black-eyed geckos are an astonishing species of gecko, capable of living in the harsh alpine zone, and must surely push the limits of reptile physiology. Live specimens have been found up to 2200 metres a.s.l and may exist even higher. Black-eyed geckos are primarily nocturnal, however, they are known to bask (usually in partial concealment) (van Winkel et al. 2018) and possibly feed during the day. Black-eyed geckos typically inhabit deeply creviced rock bluffs and tors, which likely provide safety from predators and stable temperatures throughout the winter. However, based on increased knowledge about the habitat use of the ecologically similar (and phylogenetically related) hura te ao gecko (Mokopirirakau galaxias), it is possible that they inhabit alpine/subalpine boulderfield and tallus too (pers. comm. Samuel Purdie).

Social structure

The black-eyed gecko is solitary in nature, although it is thought that they may share refugia with congeners during the winter. As is the case with other Mokopirirakau it is theorised that males likely show aggression to other males during the breeding season. Neonates (babies) are independent at birth.

Breeding biology

Largely unknown, however, as with all of Aotearoa's gecko species, the black-eyed gecko is viviparous. Additionally, as with other alpine lizards, it is thought that they give birth to one or two live young, biennially (once every two years). Mating in Mokopirirakau may seem rather violent with the male repeatedly biting the female around the neck and head area. Sexual maturity is probably reached between 1.5 to 2 years as with other Mokopirirakau, however, it may take up to 4 years in some of these alpine species.

Diet

Black-eyed geckos are omnivores. They are primarily insectivorous in nature, but are thought to feed on the nectar, and small fruits of several subalpine plant species when they are seasonally available. Being terrestrial in nature, their invertebrate prey tends to be predominantly composed of moths, spiders, weta, and other invertebrates that live in the alpine environments.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a clear determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The black-eyed gecko, as with other Mokopirirakau species, is a likely host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon poicilandri), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. In addition to this, it is known to be a host for at least one species of ectoparasitic mite - potentially Neotrombicula naultini as this species is known to occur on other members of the Mokopirirakau genus.

Wild Mokopirirakau have been found with Disecdysis (shedding issues).

Conservation

Black-eyed geckos are listed by Department of Conservation as 'nationally vulnerable' (Hitchmough et al. 2016). This species is not being actively managed, however, due to their cryptic ecology, persistence in the alpine/subalpine zone, and the availability of deep and narrow refugia, they are probably at not immediate risk of extinction. Nevertheless, periodical monitoring and surveys would be highly beneficial to monitor this species, particularly because mammalian predators are moving higher into the alpine with warming temperatures.

Interesting notes

The black-eyed gecko gets its common name from its dark eyes which are fairly unique within the Aotearoa gecko fauna. The specific name 'kahutarae' gives reference to one of the first localities where the species was found - Kahutara Saddle in the Kaikōura Ranges.

"Moko-piri-rakau" is the Maori name for forest gecko, and means 'lizards that clings to trees.'

The black-eyed gecko sits within the northern clade of the Mokopirirakau genus, with the forest gecko being its closest relative within the group, and the hura te ao gecko being more distantly related.

References

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.