- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Whitakeri

Oligosoma whitakeri

Whitaker's skink

Oligosoma whitakeri

(Hardy, 1977)

Length: SVL up to 101mm, with the tail being equal to or slightly longer than the body length

Weight: up to 26 grams

Description

A large, and highly secretive skink with intricate cream/yellow and black blotching on it's flanks. Whitaker's skinks were formerly widespread in the North Island, but are now one of our rarest lizards.

They are characterised by their yellow/brown to dark brown dorsal (upper) surfaces, which are covered with light to dark flecks which may be indistinct or very prominent. Their flanks (sides) are cream/yellow or brown, and are usually heavily mottled with black, particularly on the sides of the neck. This typical flank pattern can also be reversed with a black background colour with pale mottling. The ventral (lower) surfaces range from yellow to orange, and are usually unmarked or faintly marked; their throat is a pale grey. The tail can sometimes have an orange hue. The head is deep set with a short, blunt snout. A pale, black-edged teardrop is present beneath each eye. As with many Oligosoma species, their pattern may fade considerably with age (see image gallery).

Whitaker’s skinks are similar in appearance to the co-occurring Coromandel skinks (Oligosoma pachysomaticum). However, Coromandel skinks usually have a more heavily marked belly. Juvenile Whitaker’s skinks can appear similar to ornate skinks (Oligosoma ornatum) but have more ventral scale rows.

Life expectancy

Individuals have been known to live over 46 years in captivity (D. Keall, personal communication, October 18, 2016).

Distribution

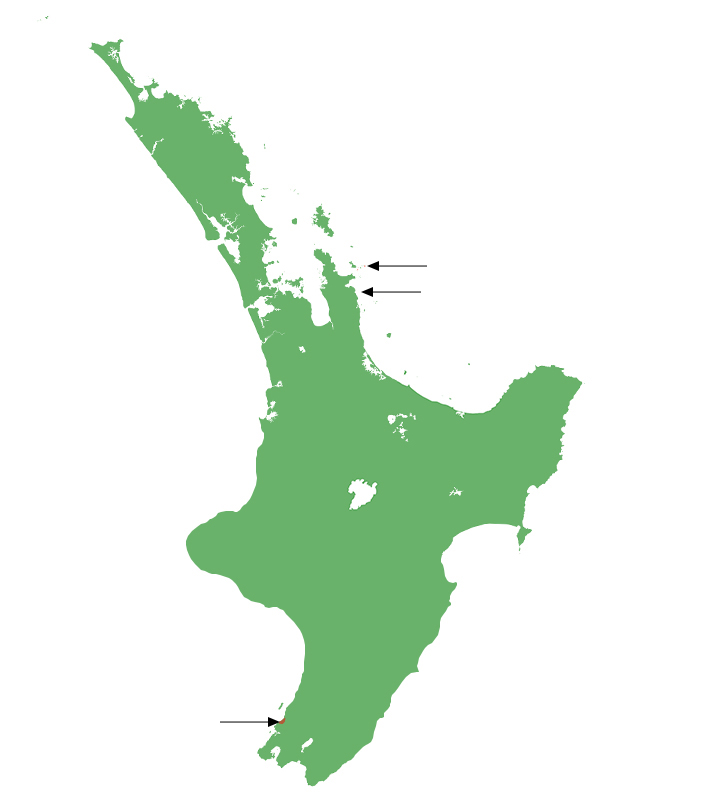

Prior to the arrival of humans and the pests they brought with them, Whitaker’s skinks were widespread in the North Island. Subfossil remains of this species have been found on Motutapu Island near Auckland, in the Waikato region, and to as far south as Wellington (Worthy, 1987).

At the time of their discovery they were only known from three locations: Middle Island (Mercury group) and Castle Island off the Coromandel peninsula; and a small population at Pukerua Bay on the mainland north of Wellington. The small population at Pukerua Bay is now presumed extinct in the wild and a small population is held in captivity as part of a breeding programme.

The species has been translocated from Middle Island to two further islands in the Mercury group: Korapuki Island in 1988, and Red Mercury Island in 1994.

Ecology and habitat

A nocturnal species, with crepuscular tendencies, being particularly active at dawn and for several hours after dusk. Whitaker's skinks are active over a very narrow climatic range, with capture rates at Pukerua Bay indicating that the temperature preference for activity is 15-20°C. Gravid females will sun bask.

Being restricted to islands, they are associated with deep leaf litter and seabird burrows in coastal forests and scrub. At Pukerua Bay the species was occupying a coastal boulder bank interspersed with patchy Muehlebeckia sp. vineland.

Social structure

Largely unknown; observations of captive animals indicate that the species prefer to live solitarily (D. Keall, personal communication, October 18, 2016). Males are likely to show aggressive behaviour towards other males, especially during the breeding season. Neonates (babies) are independent at birth.

Breeding biology

Like the majority of Aotearoa's skink species, the Whitaker's skink is viviparous, giving birth to litters of up to five young in April.

Diet

Whitaker's skinks are omnivores. They are primarily insectivorous in nature, but are known to feed on the nectar, and small fruits of several plant species when they are seasonally available. Being terrestrial in nature, their invertebrate prey tends to be predominantly composed of ground beetles, spiders, weta, and other ground-dwelling invertebrates.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a precise determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The Whitaker's skink, as with other Oligosoma species, is a likely host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon trimorphi), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. In addition to this, it is thought to be a host for at least one species of ectoparasitic mite in the Ophionyssus genus.

Conservation

DOC classify Whitaker’s skinks as ‘Threatened - Nationally Endangered’ (Hitchmough et al. 2021) due to their highly restricted range, and susceptibility to mammalian predators.

Whitaker's skinks were translocated from Middle Island to two additional pest free islands in the Mercury group (Korapuki and Red Mercury Island), to help safeguard the species.

A project is being undertaken by DOC and Friends of Mana Island to capture, breed and relocate a population of vulnerable Whitaker’s skinks from Pukerua Bay to predator free Mana Island. There is some uncertainty and concern about how Whitaker’s skinks might interact with the larger and more aggressive McGregor’s skink (Oligosoma macgregori) which are already present on the Island (subfossils indicate the two species have been sympatric in the past but no longer coexist at the same sites due to relictual distributions.

DOC have a recovery programme in place for the Oligosoma skink group, and a specific recover plan for Whitaker’s skink.

Interesting notes

Whitaker's skinks were named in honour of the renowned New Zealand herpetologist Anthony (Tony) Whitaker.

Whitaker's skinks were once widespread in the North Island, but only three small populations survived following the introduction of mammalian predators, and they are now one of our rarest lizards.

Genetic studies have shown that there is little genetic divergence between populations of Whitaker's skinks on islands in the Coromandel area, and those which occured on the mainland near Wellington (Chapple et al., 2008). This suggests that there was substantial gene flow across their range prior to their decline due to mammalian predators.

The Whitaker's skink, along with its sister taxa (the marbled skink and Coromandel skink) sit within clade 4 (the teardrop skink complex) of the Oligosoma genus, with the Hauraki skink being their closest relative within the group.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.