- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Homalonotum

Oligosoma homalonotum

Chevron skink | Niho taniwha

Oligosoma homalonotum

(Boulenger, 1906)

Length: SVL up to 146mm, with the tail being longer than the body length(1.5x)

Weight: up to 40 grams

Description

A large, distinctive, beautifully-patterned and iconic skink from the outer Hauraki Gulf Islands. Niho taniwha / Chevron skinks are New Zealand's longest lizard reaching up to 35cm in total length (mainly by virtue of their tail which can be around 1.5 x their SVL / body length).

Their dorsal (upper) surface and flanks may be grey through to a light reddish brown, with darker distinctive chevron markings present along tail and back (apexes point towards head). Flanks have small pale blotches. Ventral (lower) surface pale yellow to pinkish-yellow with scattered spots, spots are most concentrated on throat which may be flushed with bright pink or red-orange colouration. Chevron skinks have a distinctive pattern of denticulate black and white stripes running along the lips, including a pale black edged ‘teardrop’ shape below they eye. The pattern of blotches on the face and throat are unique and can be used to distinguish individuals within populations.

Adult chevron skinks are distinctive and unlikely to be confused with other species. Juveniles may be confused with ornate skinks, but can be distinguished by their proportionally long tail with chevron markings, and proportionally longer snout.

Life expectancy

Little is known about the longevity of chevron skinks. However, a wild born skink which was caught as an adult, has been held in captivity since 1997 (Dave Laux, pers. comm, 07 June 2022). Thus, it is estimated that longevity of the chevron skink is at least 30 years, but probably longer. Another wild-born male, caught as an adult, was held in captivity for approximately 15 years between 1985-2000 (K. Neilson, personal communication).

Distribution

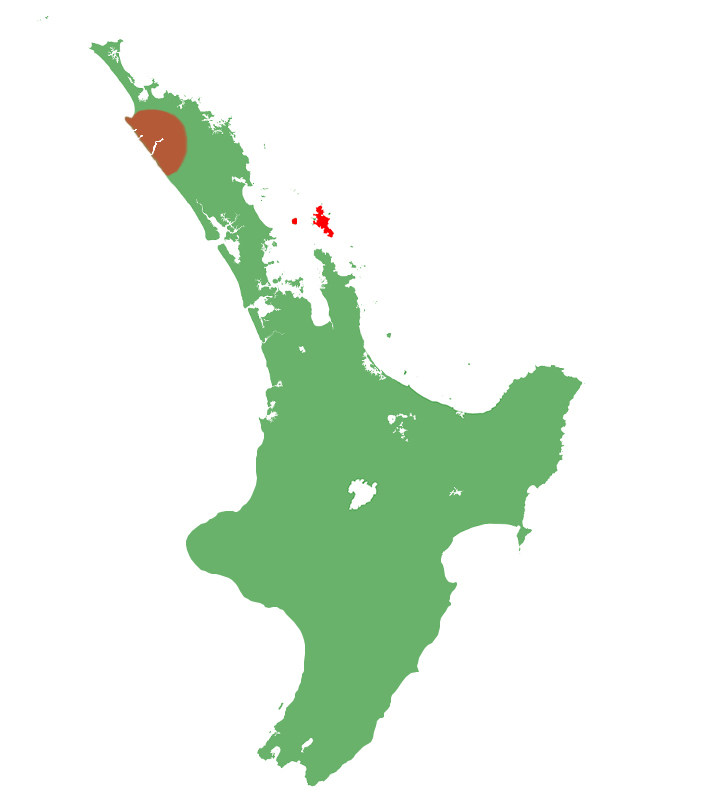

Aotea / Great Barrier Island and Te Hauturu-o-Toi / Little Barrier Island in the Hauraki Gulf. Recently, a population was discovered on 564 ha Motu Kaikōura Island (80m off Aotea) by Xyra Stannard (Clint Stannard, pers. comm, 16 October 2025).

Chevron skinks are believed to be 'pseudo-endemic' to these islands, as historical accounts and a single preserved specimen held at Auckland Museum indicate they previously occurred on the mainland north of Auckland.

Ecology and habitat

Chevron skinks are diurnal but highly cryptic. They are rarely observed foraging in the open, but will occasionally be seen basking in patches of sunlight near a retreat.

They are prone to evaporative water loss, so prefer thermally stable refuge sites. They are often associated with stream margins in native forests where they will live under rocks and logs, in crevices and burrows on stream banks, or in debris dams. Chevron skinks may also live under natural or anthropogenic debris in more open sites, and have even been found inside houses or garden sheds on Aotea / Great Barrier Island.

Chevron skinks have strongly prehensile tails and are excellent climbers. They are known to climb trees during heavy rain/flooding and often hide in tree ferns where their chevron pattern provides excellent camouflage amongst the dead fronds.

Chevron skinks are also known to dive into streams and hide underwater to evade predators, they are able to hold their breath for a considerable time until the perceived danger has passed.

Social structure

Largely unknown but thought to be solitary. They will often grunt or squeak if disturbed.

Breeding biology

Female chevron skinks give birth to litters of up to 8 live young in mid to late summer. It is not known whether chevron skinks breed annually or biennially.

In captivity, chevron skink females have been recorded giving birth at 2 years 11 months old (Ben Goodwin pers. comm. 2023). However, this is potentially due to accelerated growth rates in captive conditions, as maturity in New Zealand lizards may be associated more with size than age. In the wild, it has been presumed that chevron skinks may take around seven years to reach maturity, in common with other large-bodied species.

Diet

Chevron skinks are primarily insectivorous feeding on a wide range of invertebrates, with some individuals being known to tackle prey as large as the New Zealand giant stick insect (Argosarchus horridus) (Dennis Keal pers. comm. 2019). In captivity, they are also known to eat fruit, and it is assumed they likely consume the berries from native trees and shrubs (such as Kawakawa and Coprosma spp.) in the wild.

Disease

Largely unknown, but in common with other New Zealand skinks (Oligosoma spp.) it is likely that chevron skinks are the host for several intestinal parasites and at least one species of mite

Conservation

Niho taniwha / Chevron skinks are listed as ‘Threatened - Nationally Vulnerable’ in DOC's most-recent conservation status report (2021). It is presumed that they went extinct on the mainland some time during the late 1800's or 1900's, and now occupy less that 10% of their former range (currently restricted to Great Barrier and Little Barrier Islands in the Hauraki Gulf).

A research project was carried out between 1997 and 2002 to investigate habitat use and detection methods for chevron skinks, in order to better understand and protect the species (about which very little was known).

DOC also have a recovery programme in place for the Oligosoma skink group.

On Te Hauturu-o-Toi / little barrier, the island was cleared of all mammalian pests in 2004. Increased sightings of chevron skinks in the last decade suggest the species is now recovering on the island.

Chevron skinks are present in one predator-fenced sanctuary on Aotea / Great Barrier Island, but subject to predation by cats, rats, mice and pigs across most of the remainder. Several chevron skinks are also run over on the Great Barrier Island roads each year.

Interesting notes

Also known as ‘Niho Taniwha’, which translates to ‘teeth of the taniwha’ in Te Reo Māori (a reference to the distinctive chevron markings on the back).

Chevron skinks are unusually vocal for skinks, and will often grunt or squeak when disturbed.

Chevron skinks were first described in 1906, then due to mislabelling of specimens they were 'lost’ for 70 years before being rediscovered in the late 1970's on Great Barrier Island.

They were subsequently discovered on Little Barrier Island in 1991 when a single subadult male was found. This individual was held in captivity on the island for several years.

The narrow-bodied skink (Oligosoma gracilicorpus) was previously regarded as a distinct species, and known from a single (very bleached) specimen collected in the Hokianga area during the 1800's. More recent analysis of this specimen's morphology concluded it was in fact a male chevron skink, and the two species have since been synonymised. This mainland specimen, along with historical accounts of large lizards from north of Auckland matching the description of chevron skinks, provides strong evidence that the species was formerly more widespread.

The chevron skink, along with its sister taxon (the striped skink) sit within clade 5 (the arboreal skink complex) of the Oligosoma genus, with the glossy brown skink, and kakerakau skink being their closest relatives within the group.

References

Baling, M. (2003). The microhabitat use, behaviour, and population genetic structure of the chevron skink (Oligosoma homalonoum). Unpublished masters dissertation, Auckland University, Auckland, New Zealand.

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Ltd.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.