- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Naultinus Manukanus

Naultinus manukanus

Marlborough green gecko

Naultinus manukanus

(McCann, 1955)

Length: SVL up to 81mm, with the tail being longer than the body length

Weight: up to 12.5 grams

Description

A beautiful emerald green gecko species found inhabiting the Marlborough Sounds, and the adjacent Mainland. Although lacking the intricate patterning found on many of the other South Island green geckos, it makes up for its relative drabness with the uniquely raised scales that are dotted across its dorsal surfaces - a feature it shares with the closely-related rough gecko (Naultinus rudis).

In general, the Marlborough green gecko is characterised by its bright green upper surfaces, which are covered with raised and enlarged scales (sparse through to heavily present). In some individuals, these upper surfaces may be broken up by sparse white, yellow, or cream markings (either striped, blotched, or a combination of both) with thin yellow, dark green, or black outlines. Some individuals may be heavily patterned, but this is extremely rare. The sides of the animals are much the same as the upper surfaces, although rarely may be underlined by a thin white stripe. Their mouth may be bordered below by a white, or yellow stripe which terminates at the back of the mouth. As with most of our green gecko species, the Marlborough green gecko's ventral colour differs between males and females, with females having a green stomach, while males have a blue-tinged stomach.

Mouth and tongue colour can be a key feature in distinguishing between some species of South Island green gecko, although the Marlborough green gecko shares the same pattern as the starred gecko (Naultinus stellatus) with a pink/lilac mouth lining, and an orange/red tongue.

Xanthochromic (yellow) individuals are known from wild populations.

Can be differentiated from other South Island green gecko species based on mouth colour, having a pink/lilac mouth with an orange/red tongue vs. a blue mouth with a black/dark blue tongue (N. rudis, and N. tuberculatus). The raised scales are also helpful in distinguishing them from the starred gecko (N. stellatus), and the jewelled gecko (N. gemmeus), which lack this feature.

Life expectancy

Marlborough green geckos have been recorded reaching ages of ~30 years in captivity, but are likely to exceed this.

Captive green geckos have frequently been known to live for upwards of 25 years, with some individuals topping the records at 50+ (D. Keal pers. comm 2016). In the wild, green geckos have been recorded as reaching a minimum of ~15 years, although it is likely to be more than this given that the population in question was only monitored from 2009, and those animals are still alive (C. Knox pers. comm 2021).

Distribution

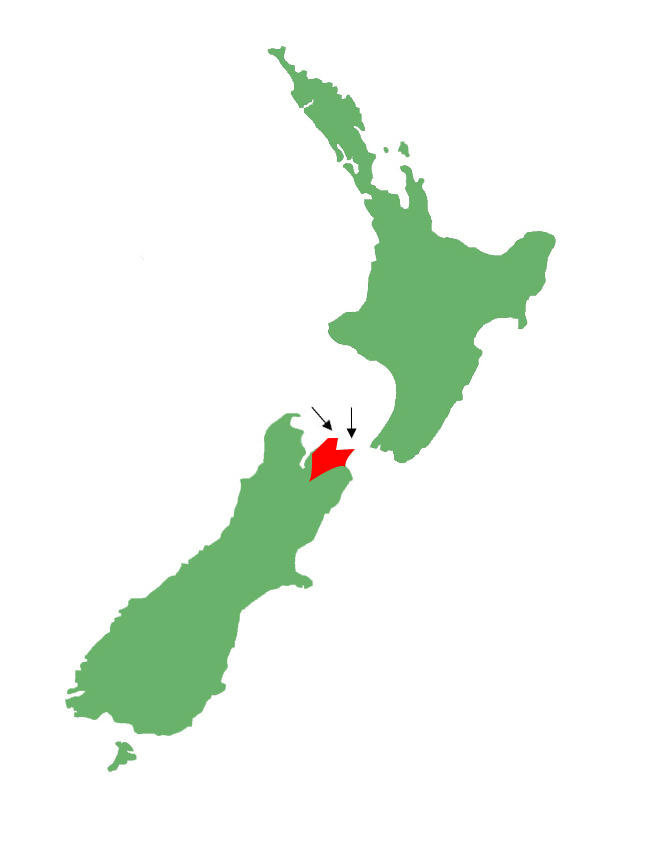

Restricted to the northern Marlborough region, bounded to the east by the Wairau River. Occurs on a large number of islands throughout the Marlborough Sounds.

Ecology and habitat

The Marlborough green gecko appears to be cathemeral (active both day and night) in nature, although predominantly considered diurnal (day-active), due to its strongly heliothermic nature (being an avid sun basker). As with all members of the Naultinus genus they are primarily arboreal (tree-dwelling), although can at times be found quite low to the ground in prostrate (ground-hugging) vegetation. Although seldom seen on the ground, males can be found travelling between trees in search of mates during the breeding season. As with all green geckos, they possess a strongly prehensile tail which acts as a third-limb/climbing aid when moving through shrubs and trees. They are known to mouth-gape and produce a barking sound as a defensive behaviour against potential predators.

Being an arboreal species, Marlborough green geckos are closely associated with forested habitats, and thus inhabit a wide variety of forest types in the Marlborough region, including swamps, scrubland, and mature forest. They appear to favour scrubby/regenerating habitats, but this may be a result of the relative ease of access, and amount of search effort that these sites garner.

Social structure

The Marlborough green gecko is solitary in nature, although can be found at fairly large densities in some habitats. Males show aggressive behaviour toward congeners, especially during the breeding season, and this is easily observable with many males showcasing scarring over their bodies. Mate guarding seems to occur in this species, with males often found in close proximity to females prior to birthing. Although independent at birth, neonates (babies) are often found together and close to the mother for the first few months of life.

Breeding biology

Like all of Aotearoa's gecko species, the Marlborough green gecko is viviparous, giving birth to one or two live young annually, from around Late February through to April. Breeding seems to occur from July through to September, with males performing mate guarding, and following females around. The gestation period is around 7.5 months.

As is the case with many lizard species, mating in green geckos may seem rather violent with the male repeatedly biting the female around the neck and head area. Sexual maturity is reached between 1.5 to 2 years.

Diet

Marlborough green geckos are omnivores. They are primarily insectivorous in nature, but are also known to feed on the nectar, and small fruits of several plant species, and the honeydew of scale insects when they are seasonally available. Being arboreal in nature, their invertebrate prey tends to be predominantly composed of flying insects (moths, flies, beetles), and small spiders.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a clear determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The Northland green gecko, as with many of our other Naultinus species, is a host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematodes in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon poicilandri), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. Similarly, it is unlikely to be a host for ectoparasitic mites in the wild. Captive collections have been known to host mites, but these have likely shifted onto the animals from different species e.g. Mokopirirakau, Dactylocnemis, and Hoplodactylus geckos.

Wild green geckos have been found with pseudobuphthalmos (build-up of liquid in the spectacle of the eye) and Disecdysis (shedding issues).

Red mites have been recorded in captive Marlborough green geckos. The bacteria Mucor ramosissimus and protozoa Trichomonas sp. and Nyctotherus sp. have also been recorded in the species. Two Marlborough green geckos have been reported as dying of mycotic dermatitis, digital gangrene and osteomyelitis.

Conservation status

Listed in the most recent threat classification as 'At Risk - Declining', due to a mix of land development/clearance of habitat, and predation by mammalian predators. Several populations are secure on predator-free offshore islands in the Sounds, however, the decline is mainly attributed to populations on the mainland, where they are much rarer.

Interesting notes

The specific name 'manukanus' references the tree/shrub mānuka, which dominates the shrubland/forests that this species is associated with. Whilst the common name refers to its regional distribution.

The Marlborough green gecko is the sister species to the rough gecko (Naultinus rudis). The starred gecko (Naultinus stellatus) is their next closest relative, whilst the West Coast green gecko (Naultinus tuberculatus) is the sister to the rest of the group.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (1996). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

Robb, J. (1980). New Zealand amphibians and reptiles in colour. Auckland, New Zealand: Collins.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.