- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Naultinus Gemmeus

Naultinus gemmeus

Jewelled gecko

Naultinus gemmeus

(McCann, 1955)

Length: SVL up to 90mm, with the tail being longer than the body length

Weight: unknown

Description

Jewelled geckos are widespread, but patchy in occurrence from Banks Peninsula southwards. Our understanding of their distribution, abundance, and habitat-use has increased markedly in recent decades, however their status in some areas such as mainland Southland is still not well understood. Adults typically grow to 72-85 mm SVL (snout vent length), and occasionally up to 90 mm SVL. The name ‘jewelled gecko’ arose from the typical pattern of diamonds on the back, although striped animals also occur in some populations. They exhibit very long tails with the tail being longer than the SVL. Total length has been recorded up to 187 mm, but is more typically 155-170 mm. Jewelled geckos are extremely variable in colouring and patterning both within and between populations across their range, but this can be loosely summarised as follows:

Banks Peninsula and Canterbury Plains

Dorsal (upper) surface of females is typically a bright green or olive (rarely brown) with rows of white, cream, yellow, light green, or brown diamonds or continuous stripes, while the ventral (lower) surface is pale grey to green/yellow. Most males are usually grey/brown all over (rarely green) with similar diamond or striped markings to the females. Lining of mouth is pink or mauve. Tongue pink/orange with some individuals having a dark grey base to the tongue

South Canterbury

As above for Banks Peninsula populations except only green males and green females have been recorded (no evidence of brown/grey coloured individuals from several hundred examined). Individuals are often a very light or lime green in dorsal colouration and can have white, brown, or yellow diamonds or stripes (sometimes only very faint dorsal stripes).

Mackenzie Country and north-west Otago

These jewelled gecko populations are somewhat intermediate between populations on Banks Peninsula and those on Otago Peninsula in some respects. For example, there is an almost even mixture of both green and grey/brown coloured males; whereas all females appear to be green in base colour. Dorsal patterning usually consists of white or yellow rows of diamonds. The dorsal surface can appear quite mottled with different shades of green with or without brown patches, especially in populations in and around beech forest. A population in north-west Otago looks similar to the Mackenzie Country form, but no brown/grey individuals have been found thus far.

Coastal Otago populations (includes Otago Peninsula and eastern North Otago)

Dorsal surfaces a bright green or emerald green with rows of diamond shaped patches or narrow stripes along the length of the body. Stripes or diamonds may be cream, white, brownish, or yellow. Lining of mouth mauve or deep blue with a pink-blackish tongue.

Inland Otago populations (Lammermoor area and western North Otago)

Similar to coastal Otago populations in some respects with all individuals appearing to be green in base colouration. Many individuals, however, are a vibrant (near luminescent) green and possess whitish-green through to bright lime green diamond patterns. Striped individuals do not appear to be present unlike in the coastal Otago populations. Most individuals and populations appear to be resident in tussock grassland, but may also use native shrubs where present in gullies.

Foveaux Strait form

Confirmed on Codfish Island and Green Island in Foveaux Strait and could be present on other southern islands, Stewart Island, or less likely mainland Southland. Plain green with no markings on the dorsal surface. May have faint head markings.

Life expectancy

Captive animals can reach ages of 20-25 years, but expected to be in excess of 35 years. Several adults jewelled geckos have been monitored from 2009-2020 on Otago Peninsula, meaning that they are likely to be a minimum of 14-15 years.

Distribution

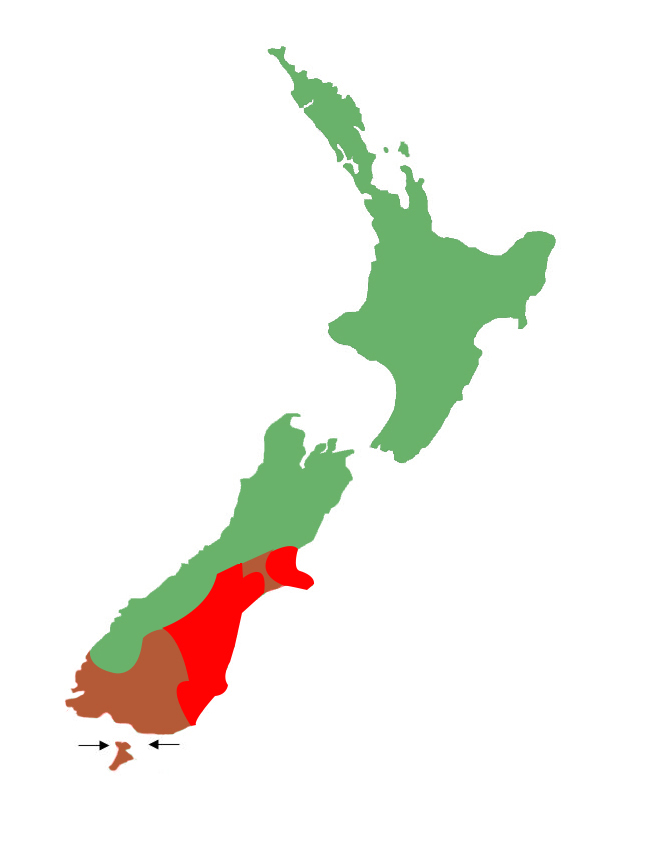

Eastern South Island from Canterbury southwards and across to close to the main divide in some places. The best-known populations are located on Banks Peninsula, South Canterbury, the Mackenzie Basin, the Waianakarua area and Kakanui Mountains across to the Ida Range, Lammermoor/Lammerlaw Range, Otago Peninsula, and Codfish Island. Translocated populations have been established, or are establishing, at Ōrokonui Ecosanctuary (Dunedin) and Mokomoko drylands sanctuary (Alexandra).

Ecology and habitat

Jewelled geckos are an arboreal or terrestrial species which can be sighted basking in the foliage of tussocks, shrubs, vines, or trees. They typically inhabit indigenous forests, shrublands, and tussock grasslands. Primary habitats include beech forest, podocarp forest, tussock grassland, and structurally-complex shrublands and vinelands ( particularly manuka, kanuka, small-leaved Coprosma sp., Muehlenbeckia spp. totara, and matagouri). Coastal and/or low altitude populations are primarily arboreal, spending little time at ground level. Inland high-altitude populations (e.g. Lammermoor Range, Ida Range, and high-altitude parts of the Mackenzie Basin) are more terrestrial in nature with narrow-leaved snow tussock being the most frequented vegetation and most individuals being sighted <0.5 metres above the ground.

Social structure

Largely unknown, as with other Naultinus species males exhibit aggressive behaviour towards other males, especially when in the presence of females. Most individuals appear to be solitary and aggregations of individuals are rarely seen. Young usually disperse away from the tree/shrub in which they were born within the first 18 months of life.

Breeding biology

Females in the Canterbury region typically give birth in spring, whereas young are typically born in late autumn in the Otago region. Births on Otago Peninsula have been recorded between late February and early June, and rarely in September. Mating has been observed on Otago Peninsula or at Ōrokonui Ecosanctuary in July and September. Births have been observed at Ōrokonui Ecosanctuary in both autumn and September. Captive animals in the Wellington region have been recorded as giving birth in February/March (D. Keall, personal communication, September 22, 2016).

Diet

Invertebrates, fruit, and nectar. Jewelled geckos on Otago Peninsula have been observed feeding on moths, harvestmen, and spiders (at night), plus butterflies and flies (by day). In addition, jewelled geckos often defecate prey items when being handled such as beetle carapaces and seeds from Coprosma propinqua berries.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a clear determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The jewelled gecko, as with many of our other Naultinus species, is likely to be a host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus, and at least one strain of Salmonella. Similarly, it is unlikely to be a host for ectoparasitic mites in the wild.

In captivity, jewelled geckos have been recorded with the ectoparasitic mite Neotrombicula naultini, but this is likely the result of a host switch that has occurred in captive situations, where other species have been co-housed or housed in close proximity e.g. Mokopirirakau, Dactylocnemis, and Hoplodactylus geckos - all are known hosts for this mite species.

Wild green geckos have been found with pseudobuphthalmos (build-up of liquid in the spectacle of the eye) and Disecdysis (shedding issues).

Conservation strategy

DOC classify the species as 'At Risk-Declining' (Hitchmough et al. 2016). Survey work in recent decades has shown that the species is still widespread and abundant at some sites; however, the species still faces many threats and is of some conservation concern. A major threat to remaining jewelled gecko populations is habitat loss, as their habitats are not always recognised or adequately protected. Habitat loss comes in many forms including clearance for agriculture, aerial spraying of shrublands (e.g. to control gorse and broom – which are often mixed in with native shrubland), exotic plantation forestry (shading out indigenous shrubland or tussockland), weed proliferation outcompeting native plants used by jewelled geckos, climate change altering vegetation composition, and fire (including tussock and grey shrubland burn-offs by farmers). Other significant threats are thought to be predation by introduced mammals – particularly in fragmented habitats (mice, rats, and mustelids are thought to be the most significant predators given their ability to climb and penetrate dense foliage), and predation from birds may be significant in some habitats. Illegal collection is a concern at some of the smaller most accessible populations, but is not presently a significant threat to the species as a whole, given the large area they occupy and the difficulty in locating individuals in many habitats. Thankfully, there are large populations of jewelled geckos in remote areas that are not easily accessible to the public.

Interesting notes

The Latin name 'gemmeus' along with its common name refers to the jewel/gem-like markings that are often present on the dorsal surfaces of the species.

Māori first described the vocalisations of green geckos to Europeans as being like kata - laughter, being a repetitive call somewhere between a bark and a squeak.

The jewelled gecko is basal (the sister species) to all other green geckos in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

Robb, J. (1980). New Zealand amphibians and reptiles in colour. Auckland: Collins.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.