- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Introduced

- Rawlinsonia Ewingii

Rawlinsonia ewingii

Southern brown tree frog

Rawlinsonia ewingii

(Dumeril and Bibron, 1841)

Length: SVL: Males up to 40mm; Females up to 50mm

Weight: unknown

Call: Cricket-like, being a high-pitched trill repeated 5 or 6 times, the first note longer than those that follow.

Description

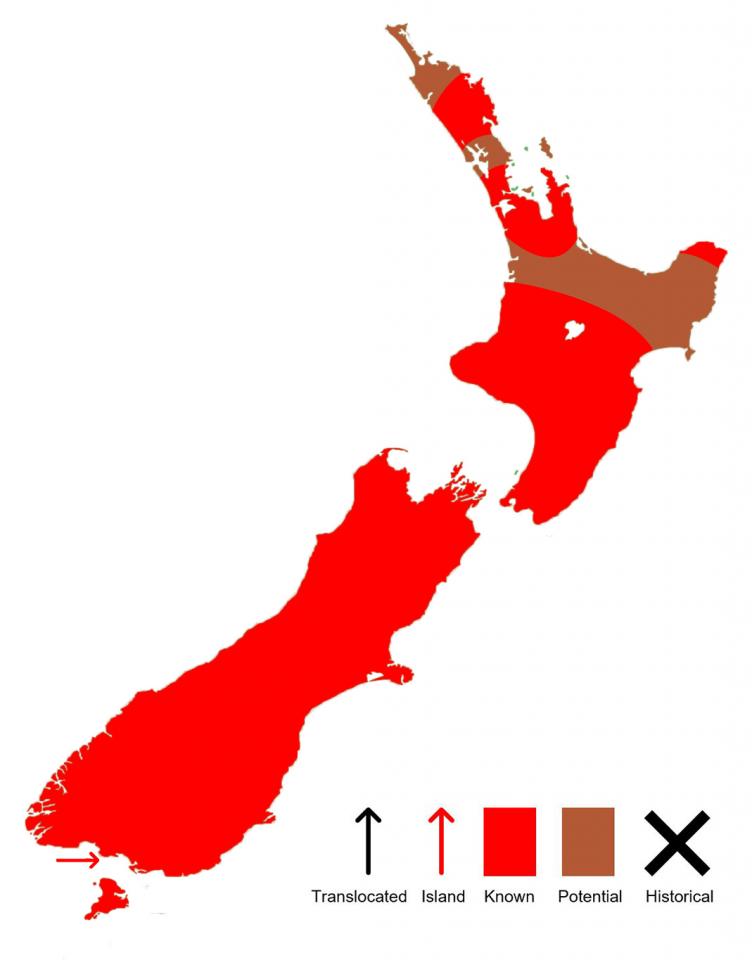

The southern brown tree frog (sometimes referred to as the whistling tree frog) is a small brown frog, being the smallest of the three Australian frog species which have become naturalised in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Originally hailing from South-eastern Australia, and Tasmania, it was deliberately introduced to Greymouth in 1875 by Mr W. Perkins, possibly with the intention of controlling pests, or as an ornamental species. They are currently distributed throughout New Zealand, south of Taupō (including Stewart Island/Rakiura, and Chatham Island/Rēkohu), despite only one recorded translocation. It is likely that this distribution is a result of multiple additional translocations (via escaped pets or intentional releases) carried out by members of the public.

Adult frogs:

The southern brown tree frog, as the name suggests, is characterised by its brown colouration, as well as by its small size. The dorsal surfaces are generally light brown in colour but can range from whitish-grey through to dark brown, often with darker pigmentation running along the back in a broad stripe from the top of a head to the tail. A dark brown stripe runs laterally from the nostril to the armpit, bordered below by a white stripe, which usually terminates below the eye (although this may reach the nostril in some individuals).

The lower surfaces of the animal are often white or cream, although the undersides of the thighs are often bright orange in colouration.

The feet of the southern brown tree frog lack webbing, but have slightly expanded toe pads which aid in climbing.

As with some other frog species, southern brown tree frogs possess some sexual dimorphism; females are often larger than males (female SVL up to 50mm, male SVL up to 40mm), and males develop a dark brown throat during the breeding season.

They can be easily distinguished from the bell frogs (Ranoidea spp.) based on colouration and size, and from our native Leiopelma frogs by the presence of an external eardrum.

Tadpoles:

The tadpoles of the southern brown tree frog, as with most frog species, resemble a small round fish which lacks fins. They are often black when first hatched, but as they get closer to metamorphosis they begin to take on the brown colouring of the adult frogs, the fin is translucent, but has a brownish tinge to it.

Tadpoles are fairly small when first hatched (~5mm) but over the following 7 weeks slowly grow to reach lengths of up to 60mm.

Life expectancy

Southern brown tree frogs are known to live for up to 5 years in captivity. Although life expectancy in the wild is not known, it is likely to be less than what is observed in captive individuals.

Distribution

The native range of the southern brown tree frog encompasses large swathes of coastal south-eastern Australia (from Sydney to Adelaide), as well as Tasmania. They were initially introduced to Greymouth, from Tasmania in 1875, but through one official translocation to Manawatu, and several further liberations by the public, they now encompass most of the country (including Stewart Island/Rakiura), except for the northern North Island (north of Taupō). A population occurring on Chatham Island/Rēkohu is likely to be a recent inadvertent introduction.

Ecology and habitat

As with most frogs, the southern brown tree frog is semi-aquatic, and as such is often seen in close proximity to water bodies (particularly during the breeding season). Although semi-aquatic, they tend to be better suited to a terrestrial/arboreal lifestyle often spending most of their time in low-growing vegetation (1-2 metres above ground) rather than in the water. They are predominantly nocturnal but are known to be active during the day, sometimes even calling from dense bushes. As opposed to the other exotic frog species in New Zealand, southern brown tree frogs can effectively be active during our winter, being able to survive freezing for short periods of time.

The physiology of the southern brown tree frog allows it to occur in a vast array of habitats throughout New Zealand, from the coastline to alpine environments. That being said they spend the vast majority of their time around ponds and streams, preferring complex habitats with plenty of climbable shrubs. Habitats that they are known from include duneland, swamps, forests, alpine and subalpine environments, roadside ditches, quarries, farmland, and urban areas.

Social structure

Southern brown tree frogs are for the most part solitary. During the breeding season (which is all year round in New Zealand), they can be found in reasonable numbers around water bodies, and are often responsive to the calls of other males, often resulting in a chorus of chirping.

As tadpoles, southern brown tree frogs tend to form aggregations similar to schooling in fish, this is likely a strategy to avoid predation.

Breeding biology

In New Zealand, southern brown tree frogs breed throughout the year (given the conditions are suitable e.g. usually following rain). During this time males will call from vegetated areas close to water bodies (ponds, slow-flowing streams, etc.). Mating itself is known as 'amplexus', in which the male clings to the back of a female, and fertilises eggs as they are released; a process that can take anywhere from 10 minutes to 5 days in other species.

As with most amphibians, the southern brown tree frog is oviparous, laying several clumps of eggs (500-700 overall), amongst submerged vegetation. Tadpoles hatch after approximately 4-9 days. The tadpole stage itself lasts for around 7-9 weeks (although it may last for up to a year depending on conditions), with tadpoles nearing metamorphosis developing back legs before their front legs. The metamorphs themselves are characterised by fully formed limbs, and the presence of a tail. They are around 13-15mm svl at this stage, and over the next month or so will slowly resorb their tail into the body, becoming miniature versions of the adult frog. Maturity is likely reached within a year, but the exact size at reproductive age is unknown for either sex, although it is likely males mature at smaller sizes.

Diet

The southern brown tree frog is insectivorous in nature, much like other small frog species. Its specific diet is not known, but it is likely that it preys upon both, small freshwater invertebrates, and terrestrial insects, spiders, and other small invertebrates. It is possible that it may take neonates of some small skink species, but this is unsubstantiated.

Tadpoles tend to be omnivorous in nature, feeding on algae, detritus (waste or debris), and bacteria. As they get larger, tadpoles may switch to a more carnivorous diet, actively taking small freshwater invertebrates.

Disease

As with many frog species worldwide, southern brown tree frog populations have been impacted by chytridiomycosis (Amphibian chytrid fungus disease) in both their native and introduced ranges. Chytridiomycosis, caused by the chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), directly impacts the outer skin of amphibians, essentially impacting, or preventing proper respiration, hydration, osmoregulation (moment of water through the skin), and thermoregulation. Symptoms associated with this include reddening of the ventral skin, the buildup or excessive shedding of skin, odd posture (legs splayed out behind whilst resting on land), lack of survival instinct (not moving away from stimulus, or seeking shelter), and loss of the righting reflex (ability to correct themselves when upside down).

Conservation status

In New Zealand, the southern brown tree frog is listed as "Introduced and Naturalised" under DOC's threat classification system, having rapidly spread through the country following its introduction in 1875. The species is still relatively common in Australia, and Tasmania and is thus classified as least concern by the IUCN.

Interesting notes

The species name "ewingii" references Reverend Thomas James Ewing (1813-1882), an amateur naturalist and collector, who called Tasmania home.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.