- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Introduced

- Ranoidea Aurea

Ranoidea aurea

Green and golden bell frog

Ranoidea aurea

(Lesson, 1827)

Length: SVL: Males - up to 60mm; Females - ≥90mm

Weight: up to 50 grams

Call: Deep guttural 3-4 syllable croak, each note descending in duration

Description

The green and golden bell frog is one of three Australian frog species that has naturalised in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Hailing from South-eastern Australia, this beautiful green frog was deliberately introduced to Aotearoa in the 1860s by the Auckland Acclimatisation Society, with the aim of controlling pests, and recreating a fauna that reminded them of home (Great Britain). Although releases were attempted throughout the country, only those in the northern half of the North Island were successful.

Adult frogs:

In general, the green and golden bell frog is what most people would consider a typical frog. The upper surfaces are smooth (not warty), and often exhibit a striking green colouration (dark green to fluorescent green), with gold or bronze patterns throughout. In addition to the bronze/gold markings, they exhibit a light cream-coloured stripe which extends laterally from the eye to the groin, bordered below by a thin black line that carries through to the nostril. A second stripe often extends from the upper lip down to the base of the front legs.

The lower surfaces are smooth, and a uniform creamy white in colouration, with the exception of the back of the thighs, and groin which exhibit a bright blue colour.

The feet of this species are characterised by the presence of enlarged toe pads (suckers), which allow them to climb. Webbing is present on the back feet, but absent from the front limbs.

Green and golden bell frogs show some significant sexual dimorphism (differences between genders), particularly in the breeding season. In general, they can be differentiated by size, with mature males (averaging ~60mm svl) being considerably smaller than females (reaching lengths ≥90mm), but, can also be distinguished by throat colouration, with mature males developing a grey to yellowish-brown tinge to their throat. However, in the breeding season, several additional characters are present. Males exhibit dark-brown nuptial pads on their thumbs (they are usually pale, and not easily visible), and develop a rusty-orange colouration on their legs, whilst females develop a blue-ish hue on their feet.

Green and golden bell frogs can be distinguished from southern bell frogs (Ranoidea raniformis) by the absence of the thin light green mid-dorsal stripe which is almost always present in southern bell frogs, and by their skin, which is smooth rather than warty.

Tadpoles:

The tadpoles of the green and golden bell frog, as with most frog species, resemble a small round fish which lacks fins.

Their colouration varies over time with newly hatched individuals being dark-olive to black, whilst individuals close to metamorphosis take on a greeny colouration much like the adult frogs, the fin is translucent, but has a yellowish tinge to it.

When hatched, the tadpoles are roughly 5-6mm long, with half of that length being the tail, but over the next 12 weeks (although it can take as long as a year) they slowly grow to reach lengths of up to 100mm before metamorphosing into froglets.

Life expectancy

Green and golden bell frogs are known to live for up to 15 years in captivity. Although life expectancy in the wild is not known, it is likely to be less than what is observed in captive individuals.

Distribution

The native range of the green and golden bell frog encompasses large swathes of coastal south-eastern Australia, from Brisbane to Melbourne. In addition to their native range, they have also been introduced to several Pacific Islands including Aotearoa/New Zealand in the 1860s, New Caledonia sometime around the late 1800s, Vanuatu sometime after the 1930s, and Wallis island in the Wallis and Futuna group potentially as late as the 1980s.

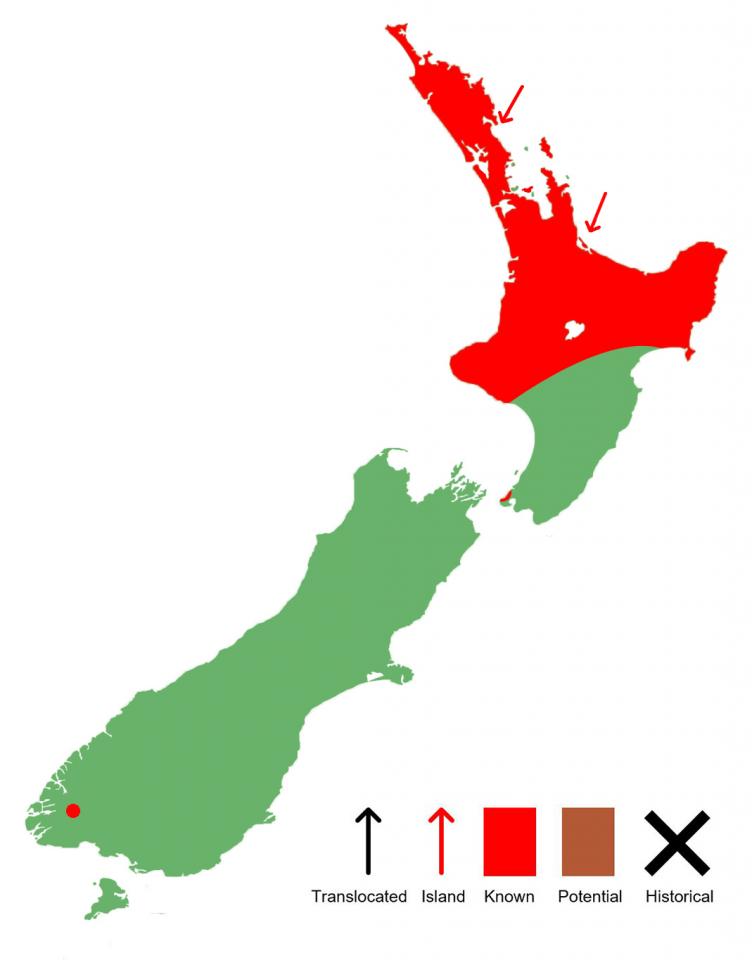

In Aotearoa/New Zealand they have spread through most of the northern North Island, following their initial releases in the 1860s, potentially assisted by further releases of unwanted/escaped pets. They now occur from about Whanganui, across to Gisborne, through to the Aupōuri Peninsula in the north. Isolated populations also occur in the Wellington region, as well as Southland.

For the most part, they seem to be restricted to the north by climatic conditions, but as temperatures warm the distribution may creep further south.

Ecology and habitat

As with most typical frogs, the green and golden bell frog is semi-aquatic, spending significant periods of time around water bodies (although they can be found relatively far from these, in some instances up to 400 metres). They are generally nocturnal in nature, however, in contrast to many frogs, they appear to be fairly active during the day, often seen basking around the edges of water bodies, or traversing land (moving up to 3km between suitable habitats). During winter they tend to enter a state of torpor, in which they eat infrequently, and are only active during suitable periods - warm weather, or after rain. Although typically found amongst reeds, and other debris at ground level, they are capable climbers and can at times be found up to 2 metres above the ground amongst vegetation.

Green and golden bell frogs are found in a wide variety of habitats but tend to be closely tied to water bodies. They are mainly found around ponds and streams but prefer complex habitats, and as such may be found in duneland, swamps, forests, roadside ditches, quarries, farmland, and urban areas with suitable water bodies nearby. They seem to be excluded from certain water bodies based on the presence of mosquitofish (Gambusia holbrooki), which are known to predate on the eggs and larvae. Additionally, if the salinity of a given water body is too high, the larval stages often fail, resulting in population crashes.

Social structure

Green and golden bell frogs are for the most part solitary, being both cannibalistic and highly territorial (especially males) in nature. During the breeding season, they can be found in large numbers around water bodies, and are often responsive to the calls of other males, often resulting in a chorus of croaking.

As tadpoles, green and golden bell frogs tend to form aggregations similar to schooling in fish, this is likely a strategy to avoid predation. When breeding ponds become overpopulated tadpoles have been known to cannibalise each other.

Breeding biology

In New Zealand, green and golden bell frogs begin their breeding season in the warmer months, between October, and March. During this time males will congregate around water bodies (ponds, slow-flowing streams, etc.), and begin calling to attract a mate. Mating itself is known as 'amplexus', in which the male clings to the back of a female (with the aid of specialised growths on the thumbs called nuptial pads), and fertilises eggs as they are released; a process that can take anywhere from 10 minutes to 5 days.

As with most amphibians, the green and golden bell frog is oviparous, laying between 3,000-10,000 eggs in a large gelatinous mass, that sinks after around 6-12 hours. Tadpoles hatch after approximately 2-5 days. The tadpole stage itself lasts for around 10-12 weeks (although can last for up to a year), with tadpoles nearing metamorphosis developing back legs before their front legs. The metamorphs themselves are characterised by fully formed limbs, and the presence of a tail, they are around 22-28mm svl at this stage, and over the next few months will slowly re-absorb their tail into the body, becoming miniature versions of the adult frog. In male frogs, maturity is reached at about 9-12 months old at 45-50mm svl, whereas females reach maturity later at around 2 years old with svl's ≥ 65mm.

Diet

Green and golden bell frogs are voracious predators, consuming a large variety of invertebrates, frogs, and lizards. Prey items are closely associated with size class, with smaller frogs often taking small flying invertebrates, while large frogs tend to focus on larger prey items. In New Zealand, bell frogs have been found to consume a wide variety of prey items, including; mosquito larvae, large terrestrial beetles, slugs, earthworms, freshwater invertebrates, small kōura, native and exotic frogs (including other green and golden bell frogs), geckos, and skinks. There have been several instances of bell frogs eating endangered species e.g. the kakerakau skink (Oligosoma kakerakau).

Tadpoles tend to be omnivorous in nature, feeding on algae, detritus (waste or debris), and bacteria. As they get larger, tadpoles may switch to a more carnivorous diet, actively taking small freshwater invertebrates, and even cannibalizing other tadpoles if their breeding pond becomes overpopulated.

Disease

As with many frog species worldwide, green and golden bell frog populations have been devastated by chytridiomycosis (Amphibian chytrid fungus disease) in both their native and introduced ranges. Chytridiomycosis, caused by the chytrid fungus (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis), directly impacts the outer skin of amphibians, essentially impacting, or preventing proper respiration, hydration, osmoregulation (moment of water through the skin), and thermoregulation. Symptoms associated with this include reddening of the ventral skin, the buildup or excessive shedding of skin, odd posture (legs splayed out behind whilst resting on land), lack of survival instinct (not moving away from stimulus, or seeking shelter), and loss of the righting reflex (ability to correct themselves when upside down).

Conservation status

In New Zealand, the green and golden bell frog is listed as "Introduced and Naturalised" under DOC's threat classification system, having rapidly spread through most of the northern North Island following its introduction in the 1860s. In contrast, the species has been listed as "Endangered" in its native range of south-eastern Australia, having seen dramatic declines since about the 1960s.

Interesting notes

The species name "aurea" references the golden markings that are present on its dorsal surfaces, the name being derived from the Latin word aureum - golden.

Aotearoa/New Zealand's populations of green and golden bell frogs are considered to be a potential backup population for this species, given that the population here is thriving when compared to the declines seen in its native range in Australia. Accordingly, the populations over here provide significant opportunities to study the species in regards to the factors that may be causing the declines in its native range.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishing.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.