Length: SVL up to 95mm, with the tail being longer than the body length

Weight: unknown

Description

A beautiful and robust species of Woodworthia with a snout-vent-length (SVL) up to 95 mm. Kōrero geckos typically have a brown or grey dorsal surface with blotches, chevrons, or longitudinal stripes. The lower surfaces of the mouth and tongue are pink; the tongue tip is often a diffuse grey. The rostral scale contacts (or nearly) contacts the nostrils.

Life expectancy

Potentially over 35 years.

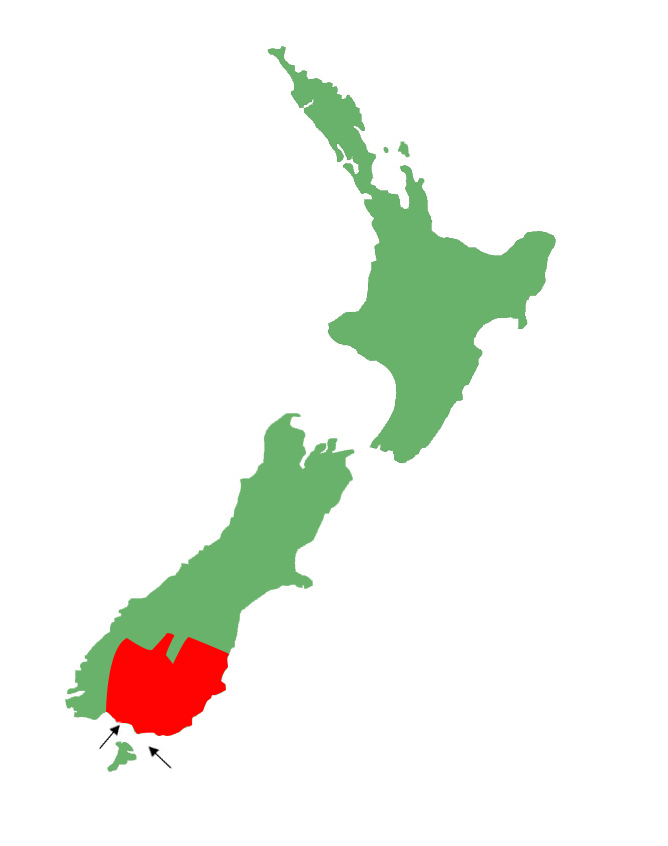

Distribution

Found throughout much of Otago, including the Dunstan Mountains, Dansey’s Pass, Kakanui Mountains, Horse Range, and Rock and Pillar Range, and Southland (including islands in Foveaux Straight).

Ecology and habitat

Kōrero geckos are terrestrial/arboreal and inhabit beech forest, podocarp/hardwood forests, rocky grasslands, and rocky alpine areas up to 1300 m (Jewell 2008) Often forms large aggregations in retreats when populations are dense. Individuals may vocalize with a chittering sound (hence their colloquial name). Kōrero geckos are recognised as a nocturnal species but exhibit a range of diurnal behaviours including basking in partial concealment, overt basking, and specific postural adjustments (Gibson et al. 2015; Gibson 2013). This is most likely to aid in thermoregulation and, in pregnant females, may result in a decreased gestation period (Gibson et al. 2015).

Social structure

A highly gregarious species that can sometimes be found in astounding densities. They can engage in antagonistic conspecific behaviour, however, typically live in large aggregations and are thus, tolerant of one another.

Breeding biology

Viviparous. Gestation approximately 14 months. Mating typically occurs in February and females store sperm over winter. Vitellogenesis (yolk deposition) typically occurs from midsummer to autumn and ovulation occurs the following spring. Embryos become fully developed by early autumn (Rock and Cree 2008; Rock 2006). In high-altitude populations, females typically breed biennially and produce up to two young in November. In lowland populations, females typically breed annually and produce up to two young in early February (van Winkel et al. 2018; Chapple 2016; Jewell 2008; Cree et al. 2003; Cree and Guillette. 2003).

Diet

Predominantly insectivorous, however, will also consume fruit and nectar sources.

Disease

Kōrero geckos are a known host for the ectoparasitic mite Neotrombicula naultini, as well as an endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus.

Conservation strategy

This species is not currently being managed by the Department of Conservation. However, in the event land is developed/destroyed, mitigation is undertaken, whereby geckos are salvaged and relocated to appropriate habitat.

Interesting notes

The kōrero gecko gets its common name from the reo word meaning 'to talk or to speak' given the vocal nature of the species. The TAG name references its distribution in the southern South Island, and its large size in comparison to many other Woodworthia found in the region.

Kōrero geckos are members of the 'common gecko' complex, a group of closely related species which are regionally distributed throughout New Zealand. Historically, most of these were considered a single highly-variable species - Hoplodactylus maculatus (the so called 'common gecko'). The 'common gecko' has now been separated into over ten different species.

The kōrero gecko, along with its sister taxa (the mountain beech and Raggedy Range geckos) sit within the Southern clade of the Woodworthia complex, with the Southern Alps gecko and greywacke gecko being their closest relatives within the group.

References

Bell, T. (2014). Standardized common names for New Zealand reptiles. BioGecko, 2, 8-11.

Chapple, D. G. (2016). Synthesising our current knowledge of New Zealand lizards. New Zealand Lizards (pp. 1-11). Springer, Cham.

Cree, A. (1994). Low annual reproductive output in female reptiles from New Zealand. New Zealand journal of zoology, 21(4), 351-372.

Cree, A., Guillette, LJ Jr. (1995) Biennial reproduction with a fourteen-month pregnancy in the gecko Hoplodactylus maculatus. Southern New Zealand Journal of Herpetology 29:163–173.

Cree, A., & Hare, K. M. (2010). Equal thermal opportunity does not result in equal gestation length in a cool-climate skink and gecko. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 5(2), 271-282.

Cree, A., Tyrrell, CL., Preest, MR., Thorburn, D., Guillette, LJ Jr. (2003) Protecting embryos from stress: corticosterone effects and the corticosterone response to capture and confinement during pregnancy in a live-bearing lizard (Hoplodactylus maculatus). General and Comparative Endocrinology 134:316–329.

Gaby, M. J., Besson, A. A., Bezzina, C. N., Caldwell, A. J., Cosgrove, S., Cree, A., Haresnape, S., & Hare, K. M. (2011). Thermal dependence of locomotor performance in two cool-temperate lizards. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 197(9), 869-875.

Gibson, S. (2014). Basking behaviour of a primarily nocturnal, viviparous gecko in a temperate climate (Doctoral dissertation, University of Otago).

Gibson, S., Penniket, S., & Cree, A. (2015). Are viviparous lizards from cool climates ever exclusively nocturnal? Evidence for extensive basking in a New Zealand gecko. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 115(4), 882-895.

Hitchmough R (1997): A Systematic Revision of the New Zealand Gekkonidae. Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Hitchmough, R., Barr, B., Knox, C., Lettink, M., Monks, J. M., Patterson, G. B., Reardon, J. T., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J., & Michel, P. (2021). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2021. New Zealand threat classification series 35. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conversation.

Jewell, T. (2006). Identifying geckos in Otago. Science & Technical Pub., Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

Lord, J. M., & Marshall, J. (2001). Correlations between growth form, habitat, and fruit colour in the New Zealand flora, with reference to frugivory by lizards. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 39(4), 567-576.

Mockett, S. (2017). A review of the parasitic mites of New Zealand skinks and geckos with new host records. New Zealand journal of zoology, 44(1), 39-48.

Mockett, S., Bell, T., Poulin, R., & Jorge, F. (2017). The diversity and evolution of nematodes (Pharyngodonidae) infecting New Zealand lizards. Parasitology, 144(5), 680-691.

Nielsen, S. V., Bauer, A. M., Jackman, T. R., Hitchmough, R. A., & Daugherty, C. H. (2011). New Zealand geckos (Diplodactylidae): cryptic diversity in a post-Gondwanan lineage with trans-Tasman affinities. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 59(1), 1-22.

O’Donnell, C. F., Weston, K. A., & Monks, J. M. (2017). Impacts of introduced mammalian predators on New Zealand’s alpine fauna. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 41(1), 1-22.

Reardon, J. T., & Norbury, G. (2004). Ectoparasite and hemoparasite infection in a diverse temperate lizard assemblage at Macraes Flat, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of Parasitology, 90(6), 1274-1278.

Rock, J. (2006) Delayed parturition: constraint or coping mechanism in a viviparous gekkonid? Journal of Zoology 268:355–360.

Rock, J., Cree, A. (2003) Intraspecific variation in the effect of temperature on pregnancy in the viviparous gecko Hoplodactylus maculatus. Herpetologica 59:8–22.

Rolfes, J. W., & Godfrey, S. S. (2023). Seasonal and spatial patterns of infestation with ectoparasitic mites on New Zealand geckos revealed using a crowd-sourced citizen science database. Austral Ecology, 00, 1-8.

Spitzen–van der Sluijs, A., Spitzen, J., Houston, D., & Stumpel, A. H. (2009). Skink predation by hedgehogs at Macraes Flat, Otago, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 205-207.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.

Wiedemer, R. L., Wilson, D. J., Mulvey, R. L., & Clark, R. D. (2007). Sampling skinks and geckos in artificial cover objects in a dry mixed grassland—shrubland with mammalian predator control. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 169-185.

Worthy, T. H. (1998). Quaternary fossil faunas of Otago, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 28(3), 421-521.