- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Woodworthia Cf. Brunnea

Woodworthia cf. brunnea

Waitaha gecko

Woodworthia cf. brunnea

Length: SVL up to 80mm, with the tail being equal to the body length

Weight: unknown

Description

A species of terrestrial gecko, with a complex rock-lichen pattern, primarily associated with the Canterbury region, and more particularly Banks Peninsula. Generally, this is the first species of gecko that Cantabrians become familiar with given its terrestrial nature (can be found under things on the ground), and its propensity to enter houses.

The Waitaha gecko is characterised by its largely grey to brown, rock-like dorsal colouration, which is often broken up by thick black speckling and irregular lichen-like markings, which primarily consist of a mix of black, white, and grey patches. As with many other gecko species these may appear as chevrons, blotches, transverse bands, or longitudinal stripes, which are often at least partially outlined by darker pigments (black or dark brown).

The lateral surfaces of the gecko are much the same as the dorsal surfaces, although, a canthal stripe (between the nostril and eye) is often present.

The ventral (lower) surfaces are usually plain and pale but may be dotted with dark pigments in some individuals.

The Waitaha gecko is also characterised by a pink mouth colouration with a pink/grey tongue.

In comparison to most of our gecko fauna which are fairly arboreal (tree-dwelling) in nature, the Waitaha gecko spends a significant amount of time on the ground, and as such its toe pads appear much thicker than the gracile toes of other genera (e.g., Naultinus, Mokopirirakau, and, Dactylocnemis).

The Waitaha gecko is generally difficult to distinguish from other Woodworthia species where their ranges abut, however, there are several characteristics that may be useful for differentiation. In general, Waitaha geckos are larger and more robust than the other Woodworthia in the region (≤80mm vs. ≤70mm) with some species such as the pygmy gecko (W. "pygmy"), and minimac gecko (W. "Marlborough mini) being much smaller (≤60mm). Additionally, they can be differentiated from the greywacke gecko (W. "Southern Alps northern"), and Southern Alps gecko (W. "Southern Alps") by altitude (lower elevations vs. high elevations) and to some degree colouration (more brown vs. more silvery-grey).

Life expectancy

The Waitaha gecko holds the New Zealand record for the oldest known gecko found in the wild at ~53 years. The gecko in question was already an adult when first captured 50 or so years prior, and thus it is possible that the gecko could have been much older than the 53 years that was assigned to it.

Distribution

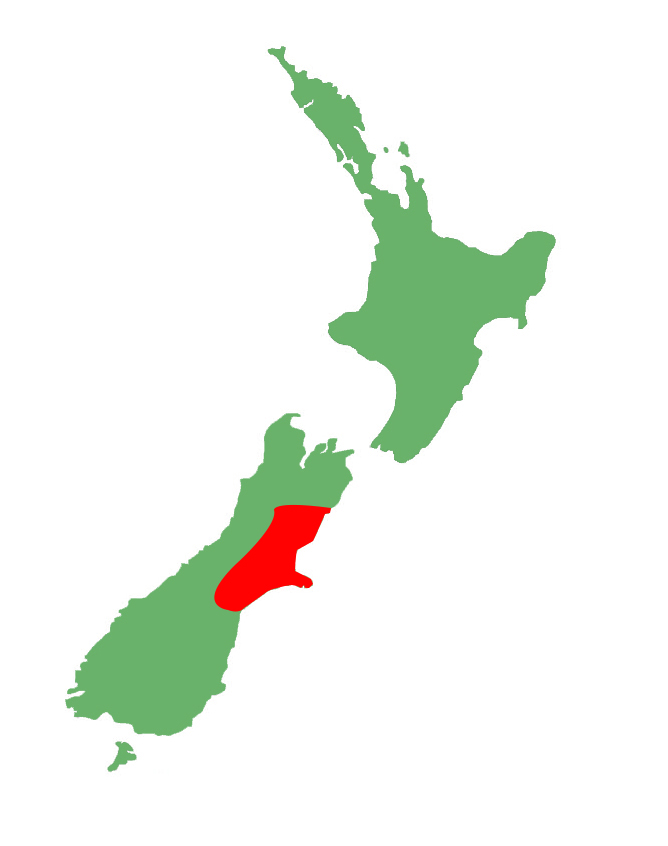

Restricted to the mid-eastern South Island between southern Marlborough (possibly bounded by the Waiau Uwha River), and lower Canterbury (possibly as far south as the northern banks of the Waitaki River). Locations of note for this species include Banks Peninsula and Mutunau Island.

Ecology and habitat

The Waitaha gecko is nocturnal in nature, although can often be observed cryptically basking (with a small part of the body exposed) at the entrances to their retreats. As with nearly all members of the Woodworthia genus they are primarily terrestrial (ground-dwelling), although at times can be found between heights of 1-4 metres up in trees in search of food or shelter.

Waitaha geckos are lowland generalists, inhabiting a range of habitats including rocky outcrops, bluffs, rock tumbles, scrubby vegetation, duneland, as well as living and dead forest trees. The species exhibit high site fidelity with very small home ranges. They are known to cohabit retreats with large wētā species including the Canterbury tree wētā (Hemideina femorata) and the Banks Peninsula tree wētā (Hemideina ricta).

Social structure

They are tolerant of conspecifics, often forming aggregations of up to 12 animals.

The Waitaha gecko is for the most part solitary in nature but appears to be fairly gregarious, or at least tolerates conspecifics when utilising refugia (rock cracks, hollow logs, etc.) with upwards of 20 individuals found in suitable sites. It is likely that males show some aggressive behaviour towards other males during the breeding season, with some individuals showcasing scarring on the body during this time. Neonates (babies) are completely independent at birth.

Breeding biology

Like all of Aotearoa's gecko species, the Waitaha gecko is viviparous, giving birth to one or two live young annually.

As is the case with many lizard species, mating in Woodworthia may seem rather violent with the male repeatedly biting the female around the neck and head area. Sexual maturity is reached between 1.5 to 2 years.

Diet

Waitaha geckos are omnivores. They are primarily insectivorous in nature, but are also known to feed on the nectar, and small fruits of several plant species, and the honeydew of scale insects when they are seasonally available. Being primarily terrestrial in nature, their invertebrate prey tends to be predominantly composed of terrestrial insects (crickets/grasshoppers, beetles, and some moth species), as well as small arachnids (spiders, harvestmen).

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a clear determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The Waitaha gecko, as with many of our other Woodworthia species, is a host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon poicilandri), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. In addition to this, they are a known host for the ectoparasitic mite Microtrombicula hoplodactyla.

Wild Woodworthia have been found with pseudobuphthalmos (build-up of liquid in the spectacle of the eye) and Disecdysis (shedding issues).

Conservation status

Listed in the most recent threat classification as 'At Risk - Declining', due to a mix of land development/clearance of habitat, and predation by mammalian predators.

In 2015 and 2019, Waitaha geckos from areas in the Port Hills where their habitat was being removed, were translocated to Riccarton Bush in Christchurch to establish a new population.

Interesting notes

The Waitaha gecko is named for both its distribution and colouration. Waitaha being the reo name for Canterbury, and 'brunnea' coming from the Latin 'brūnus' meaning brown.

Waitaha geckos are members of the 'common gecko' complex, a group of closely related species which are regionally distributed throughout New Zealand. Historically, most of these were considered a single highly-variable species - Hoplodactylus maculatus (the so called 'common gecko'). The 'common gecko' has now been separated into over ten different species.

The Waitaha gecko sits at the base of the Southern clade of the Woodworthia complex, being closely related to all other southern South Island Woodworthia species (with the exception of the Short-toed gecko).

This species was originally described as Pentadactylus brunneus (Cope 1868) and taken to a French museum, but erroneously recorded as from Australia, so the name was widely overlooked in New Zealand. The type specimen was held in Paris by the Musee Jardin des Plantes. The type specimen was then obtained by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia as part of an exchange. Scientists eventually identified that this species originated in New Zealand and was common on Banks Peninsula. A French settlement was present in Akaroa during the 19th Century, which may have been why this specimen ended up in France.

References

Gill, B., & Whitaker, T. (2007). New Zealand Frogs and Reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Hitchmough, R.A., Anderson, P., Barr, B., Monks, J., Lettink, M., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., & Whitaker, T. (2012). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, in New Zealand Threat Classification Series 2. DOC: Wellington.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.