- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Zelandicum

Oligosoma zelandicum

Glossy brown skink

Oligosoma zelandicum

(Gray, 1843)

Length: SVL up to 75mm, with the tail being longer than the body length

Weight: up to 8 grams

Description

A secretive little skink from central New Zealand.

Glossy brown skinks are dark to light-brown in colouration, occasionally with tones of red. They are often tan-brown dorsally, ocassionally with lighter coloured speckling and/or an indistinct dark mid-dorsal stripe. Lateral stripes (flanks) are darker, often with light-brown or cream-coloured flecks, and may be either clean-edged (particularly in the Wellington area) or crenulated at the upper margin. The ventral (belly) colouration is often bright orange, which may extend onto the tail. Some individuals from near the shoreline may appear very dark brown or blackish in colouration.

Most individuals have pale denticulate (teeth-like) markings along the lips - a useful feature to distinguish them from the sympatric northern grass skink (Oligosoma polychroma) which can look similar. Can be similar in appearance to copper skinks (Oligosoma aeneum), but with a proportionately longer snout and often with orange (versus yellow) ventral colouration.

Life expectancy

Unknown

Distribution

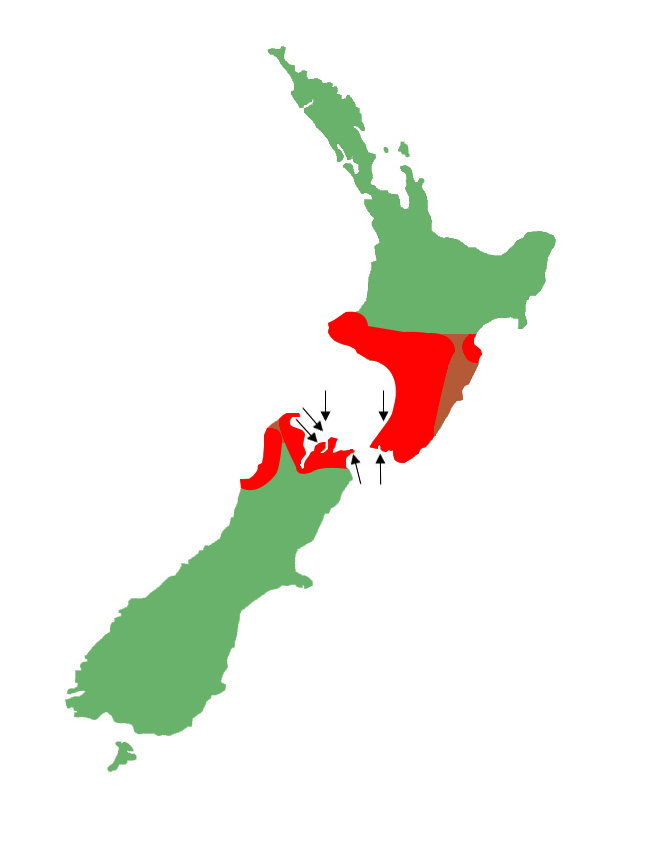

Occurs in the south-western North Island from Taranaki to Wellington. Also occurs in the South Island from Marlborough and Nelson, along the coast through the Tasman region to Westland / the West Coast of the South Island. Abundant on many islands in the Marlborough sounds.

Ecology and habitat

Glossy brown skinks are diurnal and heliothermic, but relatively secretive in habit. They are frequent sun-baskers but will often do this near a retreat and where there is shade or dense ground cover. Glossy brown skinks occur in a wide range of habitats including coastal areas near the high tide mark, in coastal pebble banks, grassland, wetland, dense scrubland, mature forest with dappled sunlight, and will also live in suburban gardens with sufficient ground cover. Glossy brown skinks show a preference for somewhat damper microhabitats than other species such as northern grass skinks (Oligosoma polychroma).

Social structure

Unknown

Breeding biology

Female glossy brown skinks usually give birth in mid-summer to litters of up to seven young.

Diet

Glossy brown skinks consume a wide range of small invertebrates. As with other New Zealand skinks, their diet likely includes berries / fruit from native plants. Glossy brown skinks have also been reported feeding on smaller lizards including baby skinks and geckos.

Disease

The glossy brown skink is a known host for the ectoparasitic mites Neotrombicula sphenodonti, and Odontacarus lygosomae.

Conservation strategy

Glossy brown skinks are currently in decline. However, large, secure populations exist on several pest-free islands and in mainland sanctuaries.

Interesting notes

Glossy brown skinks are a close relative of the critically endangered kakerakau skink (O. kakerakau). Both the glossy brown skink and kakerakau skink are members of a clade which also includes the chevron skink (O. homalonotum) and striped skink (O. striatum).

The glossy brown skink, along with its sister taxon (the kakerakau skink) sit within clade 5 (the arboreal skink complex) of the Oligosoma genus, with the chevron skink, and striped skink being their closest relatives within the group.

References

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishing.

Robb, J. (1986). New Zealand Amphibians & Reptiles (Revised). Auckland: Collins, 128 pp.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Glossy-brown skink on leaf-litter in coastal forest (Te Kakaho Island, Marlborough Sounds). © Nick Harker