- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Moco

Oligosoma moco

Moko skink

Oligosoma moco

(Duméril and Bibron, 1839)

Length: SVL up to 81mm, with the tail being much longer than the body length

Weight: up to 8 grams

Description

A distinctively striped and notoriously bold skink from the northern North Island. Moko skinks are an alert species which are a conspicuous and abundant component of many pest-free islands, but have suffered greatly on the mainland with only a handful of populations now persisting.

Head has a short, blunt snout, and eyes which are large and strikingly dark. Dorsal colour varies from light grey-brown through to dark chocolate-brown and occasionally almost black, usually with a dark mid-dorsal stripe which may break up on the tail or continue in-tact. At the edges of the dorsum (back) are distinctive cream or light-tan coloured dorsolateral stripes, which run from the snout to the base of the tail. The flanks have dark-brown lateral stripes bordered above by the dorsolateral stripe and below by a lower-lateral stripe of the same or similar colour that also starts on the head running along the margin of the upper-jaw. Dorsal and lateral stripes may be bordered with black. Ventral surfaces are grey or pale cream / fawn. When in-tact, moko skinks have a distinctively long tapering tail which is often over one-and-a-half times their body length (SVL), and slightly prehensile to aid with climbing.

Life expectancy

Unknown.

Distribution

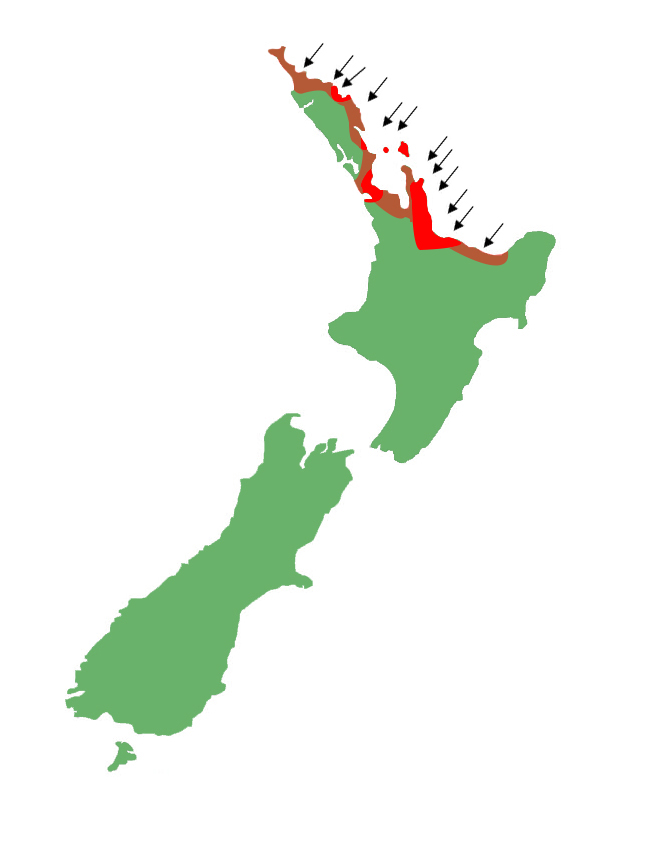

Occurs in the North Island, mainly on the east coast from the Bay of Plenty to Northland. Moko skinks are present (and often abundant) on many offshore islands, but have survived at only a small number of sites on the mainland.

Ecology and habitat

Moko skinks are diurnal and strongly heliothermic, they can often be seen basking in full sun on the edges of tracks, open areas, or in forest clearings. They are mainly terrestrial but will often climb low trees / scrub to forage above ground, individuals have even been spotted over 3 metres above ground in cabbage trees (Cordyline australis), (Tim Harker personal communication, 2020). They usually occupy areas of coastal forest, scrub, and grassland, where they often take refuge under rocks and logs, or in dense vegetation such as rank grass, flax (Phormium spp) and Muehlenbeckia spp.

Social structure

Moko skinks are regarded as solitary, but often occur in high densities at pest-free sites.

Breeding biology

Female moko skinks breed annually producing litters of one to six young from February to March. Juveniles are independent from birth.

Diet

Moko skinks are omnivorous feeding on a wide range of small invertebrates, and the fruit/berries of native plants such as Kawakawa (Piper excelsum), Coprosma spp., and Muehlenbeckia spp.

Moko skinks have also been reported catching and consuming plague/rainbow skinks (Lampropholis delicata) (David Craddock personal communication, 2020).

Disease

Moko skinks are a known host for the ectoparasitic mite Ophionyssus scincorum. The blood parasite Hepatozoon lygosomarum has also been recorded from this species.

Conservation strategy

Moko skinks are secure on multiple predator-free offshore islands. On the mainland, a population is protected/managed by a pest-proof fence and extensive predator control at Shakespear Open Sanctuary in northern Auckland.

Moko skinks have also been translocated to several additional pest-free islands including Matakohe / Limestone Island near Whangarei (sourced from the Marotere Islands), and Rotoroa Island near Auckland (sourced from Tiritiri Matangi Island).

Interesting notes

Moko skinks get their common and scientific names from the Māori word for lizard ("moko").

Moko skinks have a deep divergence from other New Zealand skinks, and sit in their own clade (Clade 7) on the Oligosoma phylogentic tree.

There are at least three distinct clades within Moko skinks; Clade 1 (Eastern Coromandel), Clade 2 (Poor Knights, Barrier Islands, Mokohinaus, and western Coromandel), and Clade 3 (Hen and chickens group). These clades show extremely deep divergences, with these groups having been separated for 2-3 million years, pending further genetic work, they may warrant species-level distinction.

References

Hitchmough, R. A. (1977). The lizards of the Moturoa Island Group. Tane, 23, 37-46.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishing.

McCallum, J. (1980). Reptiles of the northern Mokohinau Group. Tane, 26, 53-59.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1981). Reptiles of Cuvier Island. Tane, 27, 17-22.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1982). Reptiles of Little Barrier Island. Tane, 28, 21-27.

McCallum, J., & Hitchmough, R. A. (1982). Lizards of Rakitu (Arid) Island. Tane, 28, 135-136.

Robb, J. (1986). New Zealand Amphibians & Reptiles (Revised). Auckland: Collins, 128 pp.

Towns, D. R. (1972). The reptiles of Red Mercury Island. Tane, 18, 95-105.

Towns, D. R., & Hayward, B. W. (1973). Reptiles of the Aldermen Islands. Tane, 19, 93-102.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

A heavily gravid (pregnant) moko skink basking on driftwood (Motuora Island, Hauraki Gulf). © Nick Harker