Length: SVL up to 75mm, with the tail being equal to or slightly longer than the body length

Weight: At least up to 6.34 grams

Description

A beautiful and highly variable small skink with a snout-vent-length (SVL) up to 73 mm.

Dorsal surface typically light brown, grey, or grey-brown, usually with longitudinal stripes, and/or checkerboard-like patterning. Stripes may be smooth, notched, or indistinct. Mid-dorsal stripe typically present but usually broken up on tail. Lateral surfaces typically bear a wide dark brown band that is bordered above and below with pale stripes, which may be notched or smooth. Sometimes there may be pale flecks on the dark lateral band. Ventral surface typically pale white-grey (occasionally yellow) with black speckles on the throat and chin and sometimes on the belly (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

Life expectancy

At least up to eight years in the wild (van Winkel et al. 2018)

Distribution

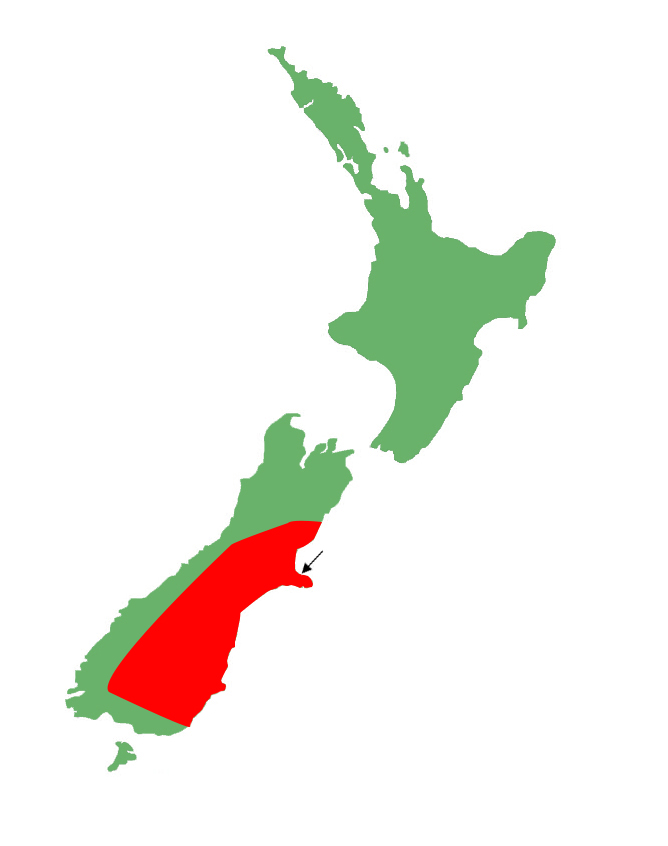

McCann's skinks are very widespread in the eastern South Island, ranging from the main divide from Canterbury to Southland.

Ecology and habitat

McCann's skinks are a diurnal, heliothermic species that can readily be seen sun-basking and hunting. This species typically occupies dry rocky environments from the lowlands up into subalpine regions. They readily inhabit rock tor systems, boulderfields, tallus, scree, rocky herbfield, exotic grasses, herbfield, and tussockland.

Social structure

McCann's skinks are somewhat solitary and don't typically form dense aggregations, however, multiple animals (i.e. more than two) can occasionally be found under suitable retreat sites.

Breeding biology

Like many other New Zealand lizards, McCann's skinks are considered lecithotrophic and begin vitellogenesis (yolk formation) in spring-autumn. Gestation typically takes 2.5-5 months and occurs between spring and summer (Holmes and Cree 2006). This species breeds annually, with mating occurring in late summer or autumn. Between December and late February 2-6 young are born. Sexual maturity is reach by 2-3 years of age (van Winkel et al. 2018).

Diet

This species will readily eat invertebrates such as spiders, millipedes, beetles, larvae, and flies. It may also eat small fruits and consume nectar from flowers.

Disease

McCann's skinks are known hosts for the ectoparasitic mites Odontacarus lygosomae, and Ophionyssus scincorum, as well as endoparasitic nematodes in the Skrjabinodon genus, and the blood parasite Hepatozoon lygosomarum.

Conservation strategy

This species is not being actively managed and is not at any immediate risk of extinction. However, land development means that this species will often have to be managed circumstantially (e.g. lizard salvages for relocation).

Interesting notes

McCann's skinks exhibit strong phylogeographic structuring and appear to form seven distinct clades. These clades are thought to have diverged during the Pliocene (O'Neill et al. 2008).

While this species is not considered threatened, habitat modification may impact this species as well as introduced mammalian predators. One study examined 158 hedgehog stomach remains and found that 21% of these contained lizard remains, many of which were McCann's skinks (Spitzen et al. 2009).

References

Caldwell, A. J., Cree, A., & Hare, K. M. (2018). Parturient behaviour of a viviparous skink: evidence for maternal cannibalism when basking opportunity is low. New Zealand journal of zoology, 45(4), 359-370.

Chapple, D. G., Ritchie, P. A., & Daugherty, C. H. (2009). Origin, diversification, and systematics of the New Zealand skink fauna (Reptilia: Scincidae). Molecular phylogenetics and evolution, 52(2), 470-487.

Cliff, H. B., Jones, M. E., Johnson, C. N., Pech, R. P., Biemans, B. T., Barmuta, L. A., & Norbury, G. L. (2022). Rapid gain and loss of predator recognition by an evolutionarily naïve lizard. Austral Ecology, 47(3), 641-652.

Cree, A. (1994). Low annual reproductive output in female reptiles from New Zealand. New Zealand journal of zoology, 21(4), 351-372.

Cree, A., & Hare, K. M. (2010). Equal thermal opportunity does not result in equal gestation length in a cool-climate skink and gecko. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 5(2), 271-282.

Daugherty, C. H., Patterson, G. B., Thorn, C. J., & French, D. C. (1990). Differentiation of the members of the New Zealand Leiolopisma nigriplantare species complex (Lacertilia: Scincidae). Herpetological monographs, 61-76.

Frank, H., & Wilson, D. J. (2011). Distribution, status and conservation measures for lizards in limestone areas of South Canterbury, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 38(1), 15-28.

Freeman, A. B. (1997). Comparative ecology of two Oligosoma skinks in coastal Canterbury: a contrast with Central Otago. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 153-160.

Freeman, A. B., Hickling, G. J., & Bannock, C. A. (1996). Response of the Skink Oligosoma Maccanni (Reptilia: Lacertilia) to Two Vertebrate Pest-Control Baits. Wildlife research, 23(4), 511-516.

Gaby, M. J., Besson, A. A., Bezzina, C. N., Caldwell, A. J., Cosgrove, S., Cree, A., Haresnape, S., & Hare, K. M. (2011). Thermal dependence of locomotor performance in two cool-temperate lizards. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 197(9), 869-875.

Hardy, G. S. (1977). The New Zealand Scincidae (Reptilia: Lacertilia); a taxonomic and zoogeographic study. New Zealand journal of zoology, 4(3), 221-325.

Hare, K. M., Caldwell, A. J., & Cree, A. (2012). Effects of early postnatal environment on phenotype and survival of a lizard. Oecologia, 168(3), 639-649.

Hare, K. M., & Cree, A. (2010). Exploring the consequences of climate-induced changes in cloud cover on offspring of a cool-temperate viviparous lizard. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 101(4), 844-851.

Hare, K. M., & Cree, A. (2011). Maternal and environmental influences on reproductive success of a viviparous grassland lizard. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 254-260.

Hare, K. M., Hare, J. R., & Cree, A. (2010). Parasites, but not palpation, are associated with pregnancy failure in a captive viviparous lizard. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 5(3), 563-570.

Hare, J. R., Holmes, K. M., Wilson, J. L., & Cree, A. (2009). Modelling exposure to selected temperature during pregnancy: the limitations of squamate viviparity in a cool-climate environment. Biological journal of the Linnean Society, 96(3), 541-552.

Hare, K. M., Yeong, C., & Cree, A. (2011). Does gestational temperature or prenatal sex ratio influence development of sexual dimorphism in a viviparous skink?. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological Genetics and Physiology, 315(4), 215-221.

Hitchmough, R., Barr, B., Knox, C., Lettink, M., Monks, J. M., Patterson, G. B., Reardon, J. T., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J., & Michel, P. (2021). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2021. New Zealand threat classification series 35. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conversation.

Holmes, K. M., & Cree, A. (2006). Annual reproduction in females of a viviparous skink (Oligosoma maccanni) in a subalpine environment. Journal of Herpetology, 40(2), 141-151.

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

Jones, C., & Bell, T. (2010). Relative effects of toe-clipping and pen-marking on short-term recapture probability of McCann's skinks (Oligosoma maccanni). The Herpetological Journal, 20(4), 237-241.

Jones, C., Moss, K., & Sanders, M. (2005). Diet of hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) in the upper Waitaki Basin, New Zealand: implications for conservation. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 29-35.

Jones, C., Norbury, G., & Bell, T. (2013). Impacts of introduced European hedgehogs on endemic skinks and weta in tussock grassland. Wildlife Research, 40(1), 36-44.

Lettink, M., & Cree, A. (2007). Relative use of three types of artificial retreats by terrestrial lizards in grazed coastal shrubland, New Zealand. Applied Herpetology, 4(3), 227-243.

Lettink, M., Norbury, G., Cree, A., Seddon, P. J., Duncan, R. P., & Schwarz, C. J. (2010). Removal of introduced predators, but not artificial refuge supplementation, increases skink survival in coastal duneland. Biological Conservation, 143(1), 72-77.

Lettink, M., & Seddon, P. J. (2007). Influence of microhabitat factors on capture rates of lizards in a coastal New Zealand environment. Journal of Herpetology, 41(2), 187-196.

Lord, J. M., & Marshall, J. (2001). Correlations between growth form, habitat, and fruit colour in the New Zealand flora, with reference to frugivory by lizards. New Zealand Journal of Botany, 39(4), 567-576.

Mockett, S. (2017). A review of the parasitic mites of New Zealand skinks and geckos with new host records. New Zealand journal of zoology, 44(1), 39-48.

Mockett, S., Bell, T., Poulin, R., & Jorge, F. (2017). The diversity and evolution of nematodes (Pharyngodonidae) infecting New Zealand lizards. Parasitology, 144(5), 680-691.

O’Donnell, C. F., Weston, K. A., & Monks, J. M. (2017). Impacts of introduced mammalian predators on New Zealand’s alpine fauna. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 41(1), 1-22.

O’Neill, S. B., Chapple, D. G., Daugherty, C. H., & Ritchie, P. A. (2008). Phylogeography of two New Zealand lizards: McCann’s skink (Oligosoma maccanni) and the brown skink (O. zelandicum). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 48(3), 1168-1177.

Patterson, G. B., & Daugherty, C. H. (1990). Four new species and one new subspecies of skinks, genus Leiolopisma (Reptilia: Lacertilia: Scincidae) from New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 20(1), 65-84.

Patterson, G. B., & Daugherty, C. H. (1995). Reinstatement of the genus Oligosoma (Reptilia: Lacertilia: Scincidae). Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 25(3), 327-331.

Reardon, J. T., & Norbury, G. (2004). Ectoparasite and hemoparasite infection in a diverse temperate lizard assemblage at Macraes Flat, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of Parasitology, 90(6), 1274-1278.

Reardon, J. T., & Tocher, M. (2003). Diagnostic morphometrics of the skink species, Oligosoma maccanni and O. nigriplantare polychroma, from South Island, New Zealand. Wellington: Department of Conservation.

Spitzen–van der Sluijs, A., Spitzen, J., Houston, D., & Stumpel, A. H. (2009). Skink predation by hedgehogs at Macraes Flat, Otago, New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 205-207.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.

Virens, J., & Cree, A. (2019). Pregnancy reduces critical thermal maximum, but not voluntary thermal maximum, in a viviparous skink. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 189(5), 611-621.

Walker, S., Wilson, D. J., Norbury, G., Monks, A., & Tanentzap, A. J. (2014). Effects of secondary shrublands on bird, lizard and invertebrate faunas in a dryland landscape. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 242-256.

Wiedemer, R. L., Wilson, D. J., Mulvey, R. L., & Clark, R. D. (2007). Sampling skinks and geckos in artificial cover objects in a dry mixed grassland—shrubland with mammalian predator control. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 169-185.

Wilson, D. J., Mulvey, R. L., Clarke, D. A., & Reardon, J. T. (2017). Assessing and comparing population densities and indices of skinks under three predator management regimes. New Zealand Journal of Ecology, 41(1), 84-97.

Wotton, D. M., Drake, D. R., Powlesland, R. G., & Ladley, J. J. (2016). The role of lizards as seed dispersers in New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 46(1), 40-65.