- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma Grande

Oligosoma grande

Grand skink

Oligosoma grande

(Gray, 1845)

Length: SVL up to 115mm, with the tail being much longer than the body length

Weight: up to 30 grams

Description

An iconic species of large skink that is highly active and stunning. SVL up to 115 mm. Grand skinks are comprised of two major geographically-separated forms. These are as follows:

1. Eastern population:

Typically larger: up to 115 mm snout-vent-length (SVL). Dorsal surface vivid black and heavily flecked with gold, yellow, cream, or greenish markings. These markings are typically short, longitudinal, and sometimes form distinctive dorsolateral stripes. Lateral surfaces vivid black, sometimes with a conspicuous lateral band with irregular edges. Lateral band typically flecked with gold, yellow, or cream markings. Lower portion of the lateral surface more heavily flecked, often becoming continuous in colour near the ventral surface. Ventral surface, including chin and throat, uniform cream or grey, sometimes with black flecks. Eye colour brown or cream, but at a glance may look black. Ear opening as large as eye. Intact tail considerably longer than body length with bold markings similar to those on the rest of the body. Very long toes with black soles of feet (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

2. Western population:

Typically smaller: up to 105 mm snout-vent-length (SVL). Eastern population considerably rarer and highly threatened. Dorsal surface vivid black and heavily flecked with gold, yellow, cream, or greenish markings. These markings often form longer thin longitudinal stripes, and can also form thick dorsolateral stripes. The colour of western grand skinks can often be very greenish or greyish, more so than the eastern population. They can also be quite drab, and are often not quite as bright in colour as the eastern population. Lateral surfaces vivid black, sometimes with a conspicuous lateral band with irregular edges. Lateral band typically flecked with gold, yellow, cream, grey, or greenish markings. Black coloration more or less restricted to upper lateral surfaces (the lateral band). Lower portion of the lateral surface more heavily flecked, often becoming continuous in colour near the ventral surface. Ventral surface, including chin and throat, uniform cream or grey, sometimes with black flecks. Eye colour brown or cream, but at a glance may look black. Ear opening slightly smaller than size of eye. Intact tail considerably longer than body length with more uniform tail. Very long toes with black soles of feet (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008).

Life expectancy

Up to at 30 years in captivity (van Winkel et al. 2018; Dennis Keall, pers. comm. 2016)

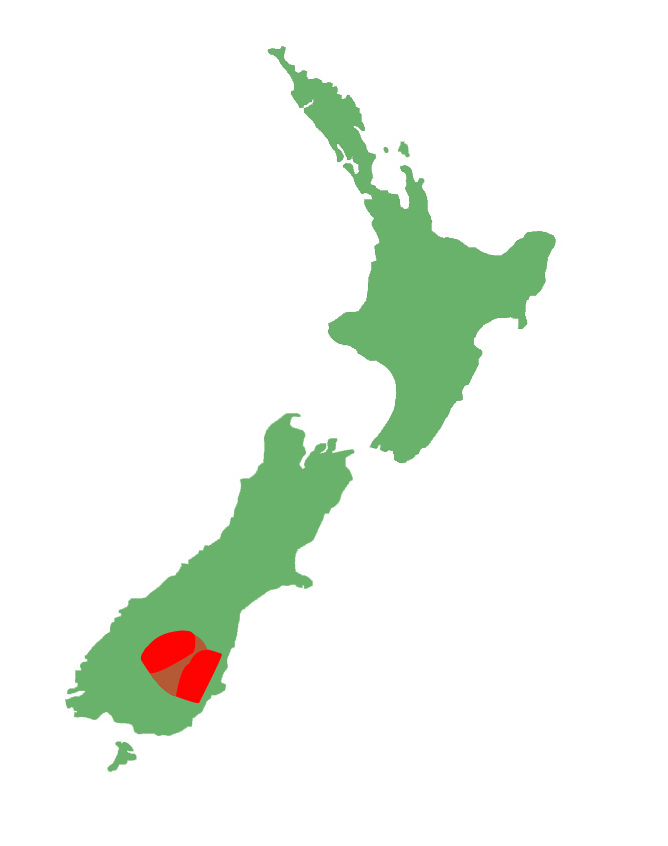

Distribution

Restricted to the Otago Region and Lakes District. Known from around Lindis Pass and Lake Hawea areas (western population), and around Macraes Flat and Middlemarch (eastern population).

Ecology and habitat

Grand skinks are diurnal, terrestrial, and primarily saxicolous. They are strongly heliothermic and avidly sun bask. The will often bask completely in the open and can maintain an unusually erect basking position. They are extremely active and have been observed moving rapidly across tor systems, and distances up to 403 metres (Whitaker unpubl. data). Grand skinks are associated with schist rock tors, especially those with native vegetation amidst or on the periphery. They seek refuge in crevices, cracks and holes in rock tors, and will forage and bask on the rocks or in surrounding vegetation (van Winkel et al. 2018; Jewell 2008). In fact, dense tussock and vegetation cover appears to be highly important for their dispersal (Whitaker 1996) and populations with limited dispersal (e.g. due to lack of complex ground cover) reportedly have higher population with less genetic diversity (Berry et al. 2005). The quality of habitat is also highly influential on metapopulation dynamics such as occupancy, colonization, and extinction probability (Gebauer et al. 2013).

Social structure

Grand skinks live in groups of up to about 20 individuals on house-sized rock tor systems. Groups are separated from other similar groups by between 50-150 m in some places (particularly where interstitial habitat is uninhabitable). In these circumstances, the relatively long distances between tors means that dispersal is limited. Adult grand skinks typically inhabit suitable tors with adult relatives of the opposite sex. In one study, 35% of potential mates were of equal relatedness as half siblings and 17% were of equal relatedness to full siblings. Grand skinks do not appear to preferentially mate with less related individuals. Accordingly, grand skinks of both sexes may indiscriminately mate, are highly promiscuous, and mate with multiple partners. Interestingly, some inbreeding does not appear to impact the survival of offspring in their first year (Berry 2006).

Breeding biology

Sexual maturity is typically reached between 3-5 years of age. Mating typically occurs from mid to late February through to late March, and possibly into autumn. Sperm is stored until ovulation, which occurs in spring. Gestation is 2-4 months with 2-4 offspring born in late summer (February-March) (van Winkel et al. 2018; Dennis Keall, pers. comm. 2016).

Diet

Grand skinks consume large quantities of small-bodied flies and native fruits such as those from Leucopogon fraseri and Melicytus alpinus. While there does not appear to be any major dietary differences between grand skinks of different age or sex, some dietary specialization between grand and Otago skinks (Oligosoma otagense) have been observed in late summer. Accordingly, habitat that lacks these plants is unlikely to be suitable (Tocher 2003).

Disease

Grand skinks are known hosts for the ectoparasitic mites Odontacarus lygosomae, and Ophionyssus scincorum, as well as the blood parasite Hepatozoon lygosomarum.

Conservation strategy

Grand skink are classified by The Department of Conservation as ‘nationally endangered’ (Hitchmough et al. 2016). DOC have a recovery plan in place for grand and Otago skinks (Oligosoma otagense) (Collen et al. 2009; Whitaker and Loh 1995) and dedicated conservation efforts have involved intensive predator control, predator-proof fences and captive breeding programs. The eradication or reduction of introduced mammalian predators appears to be highly important for the persistence of this species given their large size. Accordingly, translocations to predator-free sanctuaries and intensive trapping have been highly useful for preserving populations of this species, whereas unmanaged populations have declined severely (Norbury et al. 2014; Reardon et al. 2012; Whitmore et al. 2011).

Interesting notes

Grand skinks have been observed consuming, licking or nudging non-toxic baits. This raises the possibility that if toxic baits are accessible to grand skinks, they may consume them (Marshall and Jewell 2007). However, the impact of such an event is likely negligible to the overall population health of this species.

References

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2008). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M., Hitchmough, R. 2018. Reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand – a field guide. Auckland university press, Auckland New Zealand.