- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Hoplodactylus Duvaucelii

Hoplodactylus duvaucelii

Duvaucel's gecko

Hoplodactylus duvaucelii

(Duméril & Bibron, 1836)

Duvaucel's gecko (Coromandel). © Nick Harker

Length: SVL up to 165mm, with the tail being equal to or shorter than the body length

Weight: up to 118 grams

Description

A physically robust species with a thick head, large trunk and tail. They are the largest of New Zealand’s geckos reaching up to 160mm in snout-to-vent length, and over 30cm in total length.

Duvaucel's geckos are characterised by dorsal surfaces which are olive-brown to olive-green with pale and irregular crossbar-shaped splotches down the back, usually from the nape of the neck to the base of the tail. The underside is paler than the back, usually a pale uniform grey but can be softly blotched. Duvaucel’s gecko have a pink mouth and tongue. The forehead is slightly concave with yellow eyes and large oval openings for the ears.

Duvaucel’s gecko have a high number of lamellae on the feet with long toes (lamellae are a structure on the footpads which allow adhesion onto surfaces). Cloacal spurs (an outgrowth of bone and enlarged scales serving primarily as a grip during mating) are arranged in a series of 3-4, with pre-cloacal and femoral pores extending in a narrow series along the underside of the thighs.

There are significant genetic and morphological differences between Duvaucel's geckos and the Tohu gecko / Mokomoko a Tohu (Hoplodactylus tohu) - a separate species which occurs in the South Island: Northern Duvaucel's geckos are generally larger (110-161mm SVL), more robust, have a proportionately longer snout, and less-defined markings. Tohu geckos are generally smaller (95-120mm SVL), have a proportionately shorter snout, a more pronounced brillar fold (hood of scales above the eye), and well-defined blotched markings. Infralabial scales become gradually smaller in northern animals versus usually abruptly smaller after the 4th infralabial in southern animals.

Vocalisation of Duvaucel’s gecko has been variously described as squeaks, squeals, croaking and coughing.

Life expectancy

Duvaucel’s gecko are an extremely long lived species with ages of over 60 years reported.

Distribution

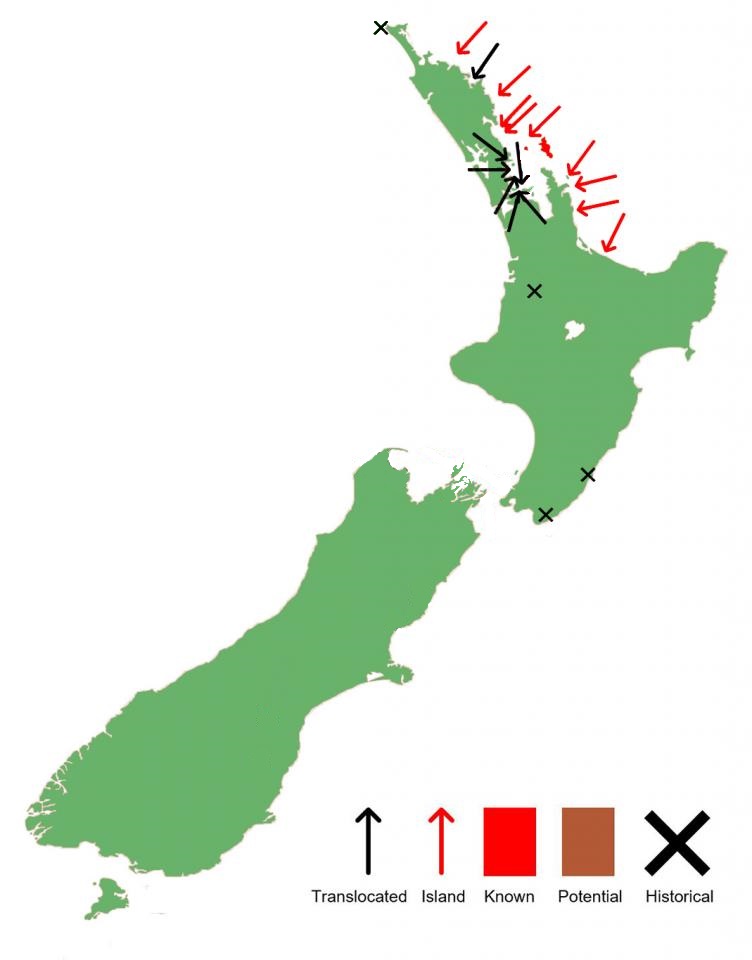

Duvaucel’s geckos were once widespread throughout the North Island of New Zealand. Unfortunately due to the impact of human settlement and the introduction of predatory mammals, the species are now restricted to several offshore islands off the east Coast of the North Island, from the Bay of Plenty northwards. They inhabit forests, bluffs, cliffs, and coastlines in lowland areas.

A related species the Tohu gecko / Mokomoko a Tohu (Hoplodactylus tohu) occurs on several islands in the Marlborough Sounds but was formerly widespread in the South Island.

Ecology and habitat

A largely nocturnal species, Duvaucel’s gecko can remain active at low temperatures but actively regulate their body temperature by sun basking. During the day they tend to hide in tree hollows, under logs, stones or bark, rock crevices or petrel burrows.

Social structure

Duvaucel’s gecko are tolerant of members of the same species and form social groups of 2-8, groups usually contain only one male.

Breeding biology

Duvaucel’s gecko give birth to live young and have a low annual reproductive output. Gestation has been variously reported as between 5 months to longer than a year. Individuals become sexually mature at about 7 years old.

Diet

The diet of Duvaucel’s gecko is largely insectivorous, however, they will also eat plant material, nectar, and fruit. There are records of Duvaucel’s gecko predating upon other lizards and the eggs of shearwaters.

Disease

Duvaucel’s gecko harbour a number of ecto and endoparasites (internal and external). In most cases ectoparasites (mites) have a negligible health impact, although heavy infestations can lead to vomiting, weight loss, tissue damage, secondary bacterial infection, or in serious cases anaemia or dysecdysis (difficulty sloughing skin).

Three species of ectoparasitic mites have been recorded on northern duvaucel's gecko, one being found in wild populations - Geckobia naultina, whilst the other two were found on captive animals, but could potentially be found in wild populations - Geckobia haplodactyli, and Neotrombicula naultini.

protozoa (Haemogregarina sp.) are also found in the blood of this species.

Conservation strategy

DOC (the NZ Department of Conservation) have classified Duvaucel’s gecko as ‘At Risk - Uncommon’, with a population of >20,000 mature individuals and a stable or increasing population (>10%).

Duvaucel's geckos have been reintroduced to multiple additional pest-free islands, and in 2016 were reintroduced to a mainland on the Tawharanui Peninsula.

Several reintroductions were established or augmented through a breed-for-release programme run by Massey University in Auckland.

Interesting notes

The species was erroneously named after Alfred Duvaucel, a French naturalist who explored India. Museum specimens taken to London were credited to him, only later were the animals found to have come from New Zealand. Today the common name and specific name (duvaucellii) can be attributed to this mistake.

Duvaucel's geckos and their sister species Moko a Tohu belong to the "broad-toed" clade of Aotearoa's gecko fauna. In this group they sit basally being the sister genera to the Woodworthia genus.

References

Fischer, S, M. (2013). Conservation biology and wildlife management in New Zealand: endemic reptile species, urban avifauna, and wetland ecology. Unpublished BSc honours dissertation. Massey University: Auckland, New Zealand.

Gill, B., & Whitaker, T. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Limited.

Hardy, G. S. (1972). A review of the parasites of New Zealand reptiles. Tuatara, 19(3), 165-167.

Hitchmough, R. A. (1977). The lizards of the Moturoa Island Group. Tane, 23, 37-46.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers.

McCallum, J. (1980). Reptiles of the northern Mokohinau Group. Tane, 26, 53-59.

McCallum, J. (1981). Reptiles of the North Cape region, New Zealand. Tane, 27, 152-157.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1982). Reptiles of Little Barrier Island. Tane, 28, 21-27.

McCann, C. (1955). The lizards of New Zealand. Dominion Museum Bulletin, 17, 1-127.

Towns, D. R. (1974). A note on the lizards of the Slipper Island Group. Tane, 20, 35-36.

Towns, D. R., & Hayward, B. W. (1973). Reptiles of the Aldermen Islands. Tane, 19, 93-102.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Whitaker, A. H. (1968). The lizards of the Poor Knights Islands, New Zealand. New Zealand journal of science, 11, 623-651.

Duvaucel's gecko on Coprosma propinqua (Tiritiri Matangi Island, North Auckland). © Nick Harker