- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Dactylocnemis Pacificus

Dactylocnemis pacificus

Pacific gecko

Dactylocnemis pacificus

(Gray, 1842)

Length: SVL up to 87mm, with the tail being longer than the body length

Weight: up to 18.75 grams

Description

A variable and often beautifully patterned species from northern New Zealand, which is notoriously nervous and fast-moving.

They are characterised by dorsal (upper) surfaces which are brown to olive green or grey with a wide variety of markings including blotches, stripes, chevrons, or bands, which are typically lighter (white, grey, or light brown) than their background colouration. Some individuals have mustard yellow spots or blotches, especially across the nape of the neck. Occasionally individuals may also have pink or orange shading. The head may have a V–shaped marking between the eyes with a wide pale stripe stretching from one ear to the other. The ventral (lower) surfaces are typically a uniform light grey in colour. The mouth and tongue are pink. Their eyes are typically brown in colouration.

Can be differentiated from the co-occurring Raukawa geckos (Woodworthia maculata) by their brighter colouration and more contrasting markings, toe width (narrow vs. wide), rostral scales (in broad contact with nostril vs. separated), and their eye colour (brown vs. green/yellow). Distinguished from forest geckos (Mokopirirakau granulatus) based on pattern (blotching vs. W-shaped markings), and eye colour (brown vs. grey).

Life expectancy

Pacific geckos have been recorded reaching ages of at least 20 years in captivity, but are likely to exceed this.

Our other gecko genera have frequently been known to live for upwards of 25 years in captivity, with some individuals topping the records at 50+ (D. Keal pers. comm 2016). The maximum age for wild animals is not known, however, it is likely that they can live at least as long as captive animals, if not longer.

Distribution

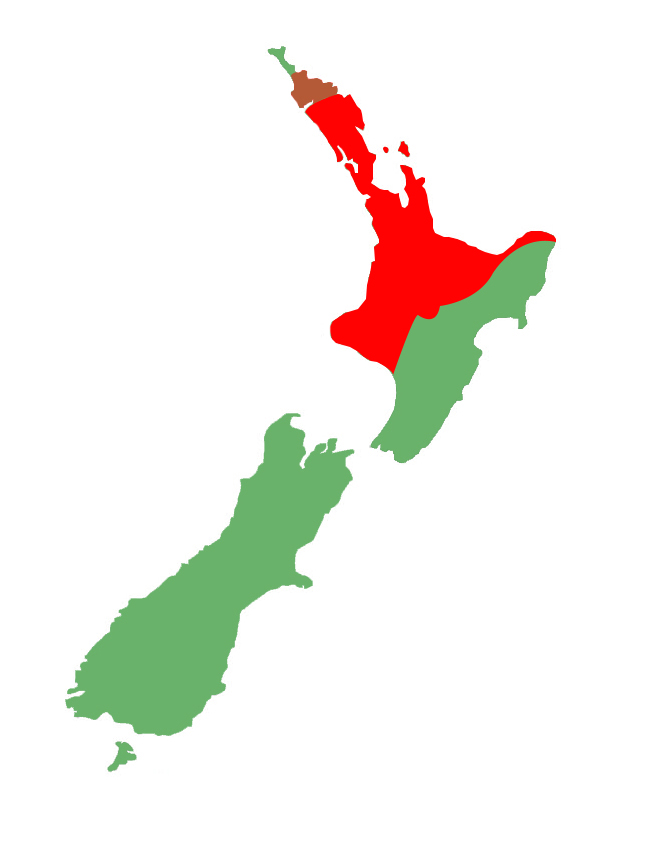

Widespread throughout the northwestern North Island (north of the Whanganui River, and northwest of the Raukumara, Te Urewera, and Kaweka Ranges). Absent in the Far North (Aupōuri, and Karikari Peninsulas) where it is replaced by the closely-related Matapia (Dactylocnemis "Matapia"), and Te Paki (D. "North Cape") geckos. Occurs on numerous islands of the northeastern coast of the North Island.

Ecology and habitat

The Pacific gecko is nocturnal (active at night), although they may cryptically bask during the day. As with many members of the Dactylocnemis genus they have both terrestrial and arboreal tendencies. They possess a strongly prehensile tail which acts as a third-limb/climbing aid when moving through shrubs and trees.

Being both arboreal and terrestrial in nature Pacific geckos are closely associated with a range of different habitats, including swamps, scrubland, mature forests, rocky coastlines, back-dunes, rocky islets, and rock outcrops. In these habitats, they often take refuge within creviced rock and clay banks, tree hollows, under loose bark, in dense ground vegetation (such as Gahnia spp.), and in epiphyte platforms (Astelia spp.) in the canopy of mature forests.

Social structure

The Pacific gecko appears to be solitary in nature, however, they can be found in large numbers cohabiting in the same refuges (especially in high-density island populations). Males show aggressive behaviour toward congeners, especially during the breeding season, and this is easily observable with many males showcasing scarring over their bodies. Neonates (babies) are independent at birth.

Breeding biology

Like all of Aotearoa's gecko species, the Pacific gecko is viviparous, giving birth to one or two live young annually from around February. As is the case with many lizard species, mating in Dactylocnemis may seem rather violent with the male repeatedly biting the female around the neck and head area. Sexual maturity is reached between 1.5 to 2 years.

Diet

Pacific geckos are omnivores. They are primarily insectivorous in nature, but are also known to feed on the nectar, and small fruits of several plant species, and the honeydew of scale insects when they are seasonally available. Having both arboreal and terrestrial tendencies, this species utilises the food sources in both habitats, preying on a mix of flying (moths, flies, beetles) and terrestrial invertebrates (wēta, grasshoppers, beetles, etc.).

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a precise determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The Pacific gecko, as with other Dactylocnemis species, is a likely host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon poicilandri), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. In addition to this, it is known to be a host for at least one species of ectoparasitic mite - Neotrombicula naultini.

Wild Dactylocnemis have been found with Disecdysis (shedding issues).

In addition to the above, they are also known hosts for trematodes (Paradisomum pacificus), and at least one protozoa in the Haemogregarina genus.

Conservation strategy

Historically the Pacific gecko was considered to be 'At Risk - Declining', however, this was updated to "Not Threatened" in the most recent threat classification. This change appears to be a byproduct of the system, as it is widely known that Pacific geckos, much like the forest gecko (Mokopirirakau granulatus), and Elegant gecko (Naultinus elegans), are experiencing declines (especially on the mainland) due to both predation by mammalian pests, and habitat loss. They appear to be fairly stable on a large number of offshore islands, and this may be the reason for their new (albeit, seemingly incorrect) threat status.

Interesting notes

The Pacific gecko gets both its common and specific name (pacificus) from the Pacific Ocean, which cradles the eastern coastline of Aotearoa.

Pacific geckos are members of the genus Dactylocnemis, a group of closely related species which are confined to the North Island of New Zealand, are regionally distributed (including several island-endemic species), and were once all considered as a single highly-variable species - Hoplodactylus pacificus. The Pacific gecko - being the earliest described species in the genus - retained the specific name pacificus.

The Pacific gecko belongs to the "southern clade" within the Dactylocnemis genus, with its sister taxa being the Poor Knights gecko, and Mokohinau gecko. The Matapia gecko also sits within this group but is more distantly related.

References

Hardy, G. S. (1972). A review of the parasites of New Zealand reptiles. Tuatara, 19(3), 165-167.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1981). Reptiles of Cuvier Island. Tane, 27, 17-22.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1982). Reptiles of Little Barrier Island. Tane, 28, 21-27.

McCallum, J., & Hitchmough, R. A. (1982). Lizards of Rakitu (Arid) Island. Tane, 28, 135-136.

Towns, D. R. (1972). The reptiles of Red Mercury Island. Tane, 18, 95-105.

Towns, D. R., & Hayward, B. W. (1973). Reptiles of the Aldermen Islands. Tane, 19, 93-102.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Pacific gecko on forest floor (Hauturu / Little Barrier Island). © Nick Harker