- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Egernia Cunninghami

Egernia cunninghami

Cunningham's skink

Egernia cunninghami

(Gray, 1832)

Length: SVL up to 250mm, with a total length of ~350mm

Weight: up to 350 grams

Description

The Cunningham’s skink is a large social skink endemic to the coastal regions of eastern Australia. Keeled scales cover the dorsal surface of their body, and this is particularly evident on their tail, giving rise to their other name, Cunningham’s spiny-tailed skink.

The Cunningham’s skink, like most skinks, has a snake-like appearance, although due to their enlarged heads, they have a more discernible neck than Aotearoa’s endemic Oligosoma. They are characterised by their spiky appearance, which is a result of keeled scales running along their dorsal surface in a series of ridges, which become larger towards the base of the tail. The tail itself is extremely spiky in appearance with large spine-like projections encircling its surface. They are fairly variable in colouration (due to their tone often matching the environment), and often have light and dark mottling consisting of various shades of brown (ranging from light brown, rust-brown, through to black) and lighter tones (subdued reds, whites or creams, and light browns), although this is much more distinctive in younger animals. Pale spots are often concentrated around their mouth as well as on their limbs and the lateral surfaces between them. The scales on the top of their heads are enlarged and have dark inter-scale colouration making them appear pronounced. Scales bordering the eye are often cream.

Lower surfaces are lighter in colouration than the dorsal surfaces, ranging from subdued reddish colour through to brown hues, with or without black speckling.

Some populations, particularly those around Girraween National Park, are strikingly patterned, often exhibiting white spots on a black background, as well as an orange/copper head and neck. These white spots can appear in horizontal lines giving a banded appearance

Unlikely to be confused with any other exotic reptile kept in captivity in Aotearoa/New Zealand due to their spiny appearance, which is particularly evident on their tail. The only other skink species held in captivity in New Zealand, the blue-tongued skink, has a considerably smoother appearance, a blue tongue, and distinct pale and dark banding.

Life expectancy

Wild animals are known to exceed 20 years but can live as long as 27 in captivity. In the wild mortality in juveniles is high, with only 33% making it through their first year of life.

Distribution

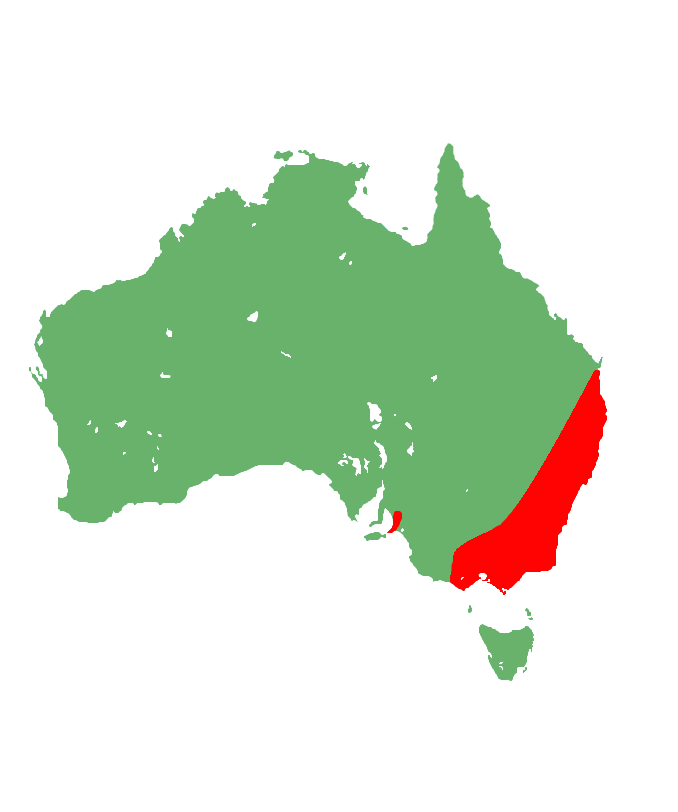

For the most part restricted to coastal regions on the eastern side of Australia from around Brisbane to Melbourne, although an isolated population also occurs around Adelaide. Predominantly restricted to rocky habitats, particularly large outcrops.

Ecology and habitat

The Cunningham’s skink is a large diurnal, saxicolous (rock-dwelling) skink, often found utilising rocky habitats, particularly large rock outcrops, where extended family groups (often an adult pair and several generations of offspring) utilise cracks and crevices for refuge from predators and environmental extremes. Once mature (at around 5 years) young animals will typically leave their colony, utilising logs and other debris in the environment for shelter as they seek out a suitable home range, although this dispersal is often quite short (<70 metres). Once a suitable home range is established (can be as little as 8m2), individuals will utilise this for the rest of their lifetime. Home range is often dictated by the available habitat, and at some sites, this leads to densities of up to 368 adults/hectare.

Although their size and highly social nature make them difficult prey for many species, particularly as adults, several species of snake are known to prey upon them including the red-bellied black snake (Pseudechis porphyriacus), and broad-headed snake (Hoplocephalus bungaroides). However, Cunningham’s skinks have a unique defence mechanism for avoiding predation within their rocky homes. Utilising their heavily keeled/spike-like scales they will squeeze into tight crevices and arch their bodies/suck in air to expand themselves, which effectively wedges them in and prevents them from being dragged out by potential predators.

As with many other species of temperate reptiles, Cunningham’s skinks enter a state of hibernation/brumation during the colder months (typically from around April to September).

Social structure

Cunningham’s skinks are some of the most social reptiles in the world, forming large long-term social aggregations of up to 26 individuals, and are often found basking together and utilising the same retreat sites. These aggregations are typically comprised of genetically similar individuals, suggesting that these are family groups consisting of an adult pair and several generations of young (juveniles may remain with their natal group for up to 5 years, until they reach maturity). Pairs are monogamous, with a high degree of mate fidelity within and between breeding seasons. Adult lizards have been shown to aggressively attack potential predators of their offspring. It has been suggested that social groupings such as those found in Cunningham’s skinks may aid in predator detection, and be a driving force for the social nature of the species.

Breeding biology

Cunningham’s skinks are viviparous (live-bearing), giving birth to 1-8 live young from January to February. Mating occurs around November. When born neonates range in SVL from 57-70mm; and reach maturity 5 years later at SVLs of 190-200mm. Cunnigham’s skinks are only known to have one litter per season/year. Being a highly social species, the family group often show some level of care for offspring. Related species have been observed assisting their offspring out of their embryonic sacs. Interestingly gravid females have been observed giving birth in the open, this may be a result of their home crevices being too narrow to allow a safe birth.

Although often found in family groups, partners are selected based on their level of unrelatedness. Seemingly one way of avoiding inbreeding is the dispersal of males once they reach maturity (females within a group are more closely related than males).

Diet

When born Cunningham’s skinks are primarily omnivorous, with a significant proportion of their diet consisting of invertebrates, however, as they mature an ontogenetic shift occurs, and they become herbivorous with 92.8% of their diet consisting of plant material.

Disease

The Cunningham’s skink is susceptible to many of the same diseases related to poor husbandry (e.g. MBD, impaction, etc.) that other captive reptiles in New Zealand can develop.

Conservation status

Cunningham’s skinks are listed as ‘Least Concern’ by the IUCN, however, in the territory of South Australia the species is restricted in its distribution and is thus considered vulnerable by the state. Their ability to disperse between populations is hindered by land clearance as they utilise debris for shelter when moving between sites.

Interesting notes

The species (cunninghami) is named in honour of the botanist and explorer Alan Cunningham (1791-1839).

Egernia and their sister genera are some of the most social reptile groups in the world with social aggregations found in at least 23 of the recognised species.