- Home

- Herpetofauna Index

- Native

- Oligosoma suteri

Oligosoma suteri

Egg-laying skink

Oligosoma suteri

(Boulenger, 1906)

Length: SVL up to 126mm, with the tail being equal to or longer than the body length

Weight: up to 26 grams

Description

A large, and enigmatic skink, beautifully adapted to the rocky littoral habitats along the northeastern coastline of the North Island. This species, along with the Fiordland skink (Oligosoma acrinasum) are probably Aotearoa's most specialised coastal reptiles.

This species is characterised by its light/golden brown to dark brown/black dorsal (upper) surfaces, which are often broken up by golden or black flecking and blotching. Vertical bands of black or dark brown blotching (which are often connected together) are concentrated along the upper edge of the lateral surfaces (sides), with the spaces in between being a mix of the dorsal colouration and the greyish tones of the lower lateral surface. The ventral (lower) surfaces are often grey, red, orange, or pink with black speckling/flecking. Occasionally individuals may be entirely black.

Can be differentiated from the co-occurring shore/tātahi skinks based on length (≤126mm svl vs. ≤80mm svl), and size, with the egg-laying skink being a significantly larger species. Also differentiated based on activity period with the egg-laying skink being nocturnal, whilst the shore and tātahi skinks are diurnal (day-active).

Life expectancy

Largely unknown, however, other Oligosoma species have been recorded reaching ages of over ten years in the wild, whilst captive Oligosoma have been reported to live for 55+ years (D. Keall, personal communication, May 22, 2021).

Distribution

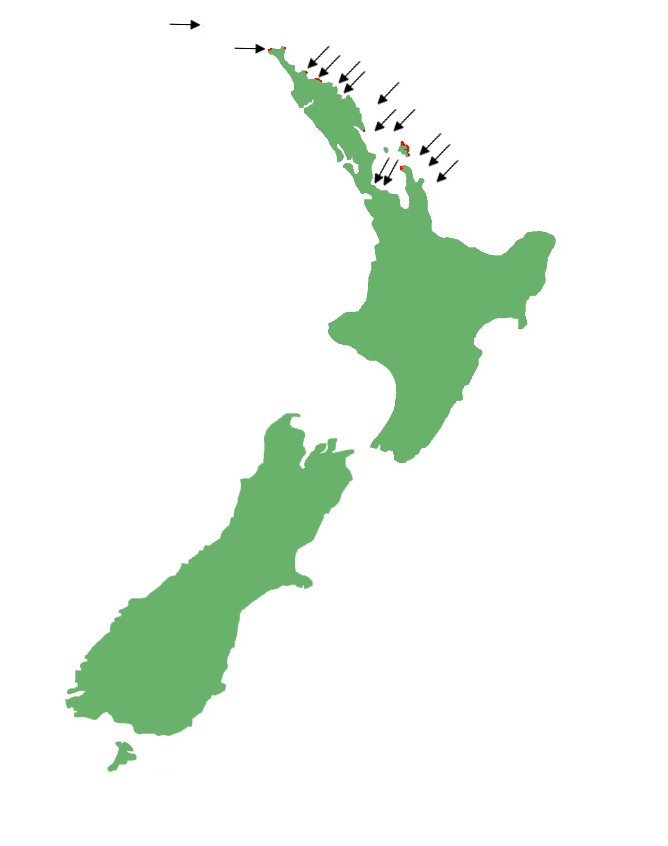

Egg-laying skinks are restricted to the east coast of the North Island from Manawatāwhi/the Three Kings Islands south to the eastern Coromandel Peninsula. There are currently only a handful of sites where the species are present on the mainland, with most relegated to offshore islands as a result of introduced predators.

Ecology and habitat

The egg-laying skink is nocturnal in nature, although they may cryptically bask within their complex rocky habitat. As with most Oligosoma, they are terrestrial (ground-dwelling), but are also saxicolous (rock-dwelling) due to their littoral habitat.

Being one of our few truly coastal reptile species, they are restricted to the interface between land and sea. In particular, they seem to be restricted to rocky coastlines (boulder beaches, rocky platforms, rocky islets, and sandy beaches with pebble banks). Due to living in this extreme environment, they have evolved several key adaptations to deal with the stress of increased salinity, and inundation of their habitat. These include the ability to secrete excess salts through specialised nasal glands, the ability to dive and swim effectively in water, and the capacity to remain underwater for extended periods of time (in excess of 20 minutes).

Due to their adaptations to the littoral zone, they are considered to be very good over-water dispersers.

Social structure

The egg-laying skink is generally considered to be solitary in nature, although they are often found inhabiting the same refugia as congeners, and can reach quite high densities in some habitats. Males are likely to show aggressive behaviour towards other males, especially during the breeding season. Females are known to communally nest, with several clutches (3-4) laid together in suitable sites. Neonates (babies) are independent upon hatching.

Breeding biology

The aptly-named egg-laying skink is Aotearoa’s only oviparous (egg-laying) lizard, laying a single clutch of ~2-5 eggs between mid-December, and mid-January. These leathery, white eggs typically hatch between 50-80 days after laying (around March/April), although during cool climatic periods (constant incubation temps ~18oC) may take up to 149 days (hatching in late-May or early June). Ovulation in adult females begins in late October.

Nest site selection is crucial to this species, as the temperature during the incubation period is the main determiner of the fitness of progeny (warmer temperatures are better). Prior to laying, females will seek thermally stable nest sites (~20-25 oC), which are protected from potential predators (hidden beneath large objects e.g., stones, wood, etc.), and oceanic disturbance (typically 2-10 metres above the high tide line). The nest itself is comprised of a shallow scrape (0-30mm in depth), and is often back-filled. Due to the scarcity of prime nesting sites in some localities, egg-laying skinks will communally nest.

Interestingly, as opposed to our only other egg-laying reptile, the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), the egg-laying skink does not have temperature-dependent sex determination, with sex instead determined by genetic factors.

As is the case with many lizard species, mating in Oligosoma may seem rather violent with the male repeatedly biting the female around the neck and head area.

Diet

Egg-laying skinks are carnivorous. They are primarily insectivorous in nature, but it is possible (although unrecorded) that they may feed on the nectar, and small fruits of several coastal plant species. They are known to forage both in rockpools, and well below the high-tide mark. In rocky habitats, intertidal invertebrates (amphipods, isopods, crabs, etc.) comprise a large proportion of their diet, whereas, on mixed sandy/rocky beaches, their diet is comprised of a mix of terrestrial and intertidal invertebrates. Foraging ceases when their body temperature drops below 8-10oC.

Due to the high sodium content of their diet, the egg-laying skink has developed specialised nasal glands to excrete excess salt from their food. In addition to this, they also excrete a large amount of sodium in their urine.

Disease

The diseases and parasites of Aotearoa's reptile fauna have been left largely undocumented, and as such, it is hard to give a precise determination of the full spectrum of these for many species.

The egg-laying skink, as with other Oligosoma species, is a likely host for at least one species of endoparasitic nematode in the Skrjabinodon genus (Skrjabinodon trimorphi), as well as at least one strain of Salmonella. In addition to this, it is known to be a host for at least one species of ectoparasitic mite in the Ophionyssus genus.

Conservation strategy

DOC classify this species as 'At risk: relict' (Hitchmough et al. 2021). Egg-laying skinks are not being actively managed and are present in moderate to high numbers on multiple predator-free offshore islands. Accordingly, they are at no immediate risk of extinction.

Although as a species they are not at immediate risk, the few mainland sites where this species does occur are severely threatened due to their susceptibility to the predators on the mainland. As such these populations should be targeted for imminent predator-control efforts in order to maintain healthy populations.

Interesting notes

The egg-laying skink along with the shore skink complex (Oligosoma smithi, O. "Three Kings, Te Paki, Western Northalnd", and O. microlepis), and moko skink (Oligosoma moco) appear to be some of the most ancient lineages in the Oligosoma family tree, being sister to every other species (excluding the Lord Howe Island skink (Oligosoma lichenigerum)).

Egg-laying skinks have extremely limited genetic divergence between populations when compared to other skink species in the same region. This may reflect their physiological constraints (unable to survive in colder climates e.g., previous glacial maximums), and their increased dispersal ability (good over-water dispersers). It is likely that the species may have been restricted to Northland during colder climates, and subsequently, as the climate warmed, dispersed along the north-to-south current that runs along the east coast of the North Island.

References

Gill, B.J., & Whitaker, A.H. (2007). New Zealand frogs and reptiles. Auckland: David Bateman Ltd.

Hitchmough, R. A. (1977). The lizards of the Moturoa Island Group. Tane, 23, 37-46.

Hitchmough, R.A., Barr, B., Lettink, M., Monks, J., Reardon, J., Tocher, M., van Winkel, D., Rolfe, J. (2016). Conservation status of New Zealand reptiles, 2015; New Zealand threat classification series 17. Wellington: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Jewell, T. (2011). A photographic guide to reptiles and amphibians of New Zealand. Auckland: New Holland Publishers Ltd.

McCallum, J. (1980). Reptiles of the northern Mokohinau Group. Tane, 26, 53-59.

McCallum, J. (1981). Reptiles of the North Cape region, New Zealand. Tane, 27, 152-157.

McCallum, J., & Harker, F. R. (1981). Reptiles of Cuvier Island. Tane, 27, 17-22.

Morris, R., & Ballance, A. (2008). Rare wildlife of New Zealand. New Zealand: Random House New Zealand.

Robb, J. (1980). New Zealand reptiles and amphibians in colour. Auckland: Williams Collins Publishers Ltd.

Towns, D. R. (1972). The reptiles of Red Mercury Island. Tane, 18, 95-105.

Towns, D. R., & Hayward, B. W. (1973). Reptiles of the Aldermen Islands. Tane, 19, 93-102.

van Winkel, D., Baling, M. & Hitchmough, R. (2018). Reptiles and Amphibians of New Zealand: A field guide. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 376 pp.

Whitaker, A. H. (1968). The lizards of the Poor Knights Islands, New Zealand. New Zealand journal of science, 11, 623-651.